What can be done about your expensive Pepco bill?

Financial assistance, energy audits, and avoiding third-party suppliers can help.

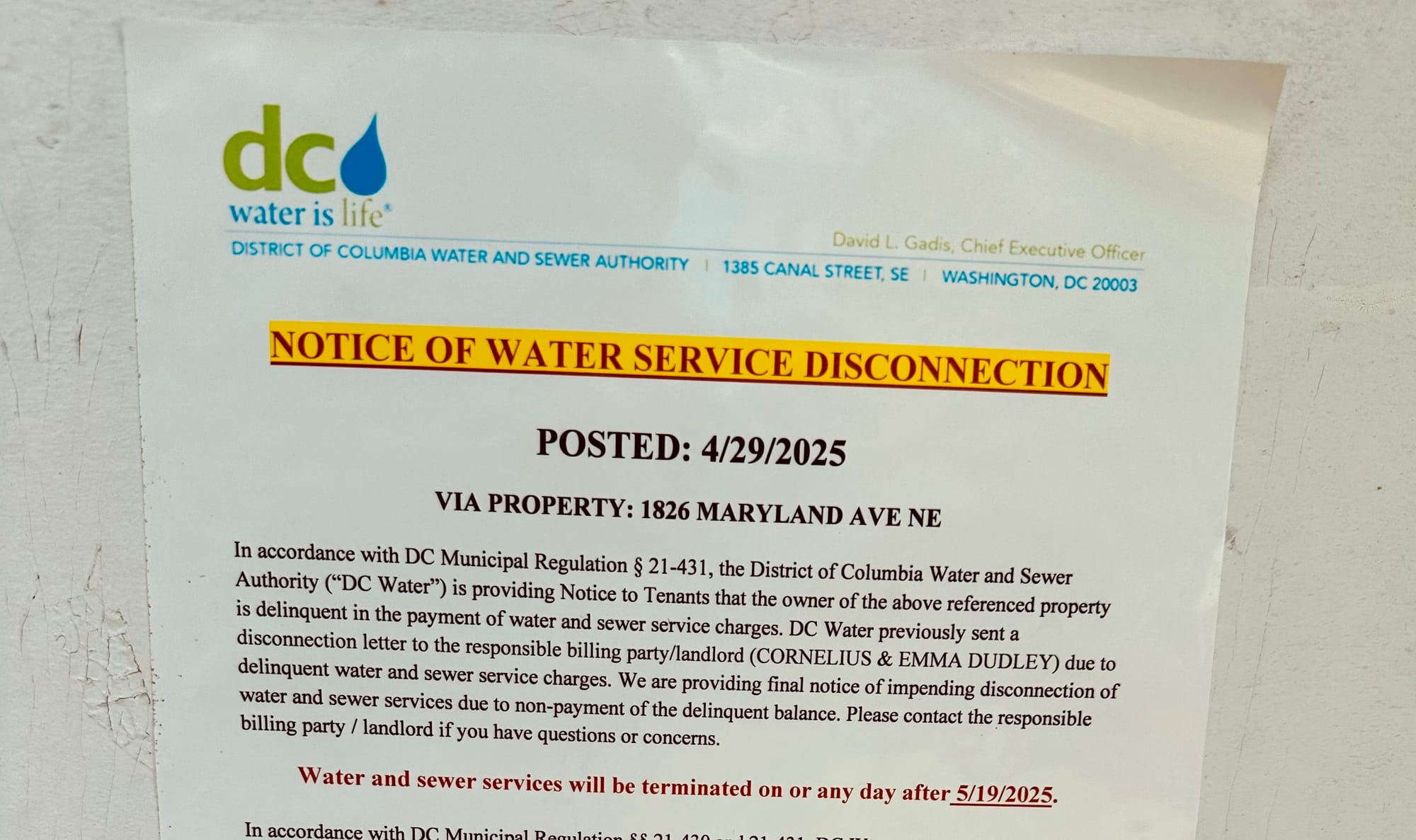

A change in policy has left renters stuck between property owners and DC Water.

Alexander Hoskins was, of all things, apologetic.

“I’ve started washing clothes like there’s no tomorrow,” he told me as we walked into his apartment on Bangor Street SE in Anacostia, stepping around piles of clothes scattered in the living room and hallway.

His laundry spree wasn’t without reason: Hoskins had just gotten his water back after a month going without it, and he wasn't sure if or when it might be shut off again.

Hoskins says he has never missed a rent or utility payment – they’ve never even been late. But the 34-year-old lives in a four-unit apartment building with a single water meter, and it is in the owner’s name. At some point, she stopped paying the bill, racking up $1,500 in unpaid charges.

In the past, DC Water would have placed a lien on the property, a step that ensures that payment is eventually made. But earlier this year, the utility changed its policy for multi-family buildings: If a bill isn’t paid, the water will be shut off – for everyone who lives there.

To date, hundreds of buildings across D.C. have received notices of pending shut-offs, and more than 100 have had their water actually disconnected.

DC Water says a significant increase in unpaid bills is to blame, and if it doesn’t take more aggressive steps, water rates will have to go up. But this also leaves renters who have no control over their building’s water bill to suffer the consequences when it’s not paid.

When Hoskins’ water was shut off at the end of May, he had to spend weeks shuttling between his girlfriend and mother’s homes in Maryland to brush his teeth, bathe himself and his four kids, and use the bathroom.

But he works nights, doing road safety on highway construction projects, so sometimes he would come home and just be forced to contend with managing daily needs without running water.

“I had no choice because I was so tired and had to use the bathroom,” he recalls. “It was a horrific ordeal.”

That ordeal dates back to March, when DC Water started executing a new policy intended to force owners of multi-unit buildings to pay overdue water bills.

Before then, the utility rarely cut off water at multi-unit buildings; in the 2024 fiscal year, it only did so three times (the practice is more common at single-family homes and commercial properties, which saw 7,000 combined shut-offs in that time period). The limited approach reflected the reality that many buildings have a single water meter in the property owner’s name, and that turning off water would impact a larger number of people.

But DC Water officials say that the new practice was borne of fiscal necessity. During a D.C. Council hearing in February, DC Water CEO David Gadis reported that unpaid water bills across the city tripled from $12 million before the pandemic to some $36 million earlier this year, 53% of which was tied to multi-unit buildings.

Officials with the utility – whose motto is “Water is life” – say that unless some of that money is recovered, rates for all customers could increase.

“As stewards of public resources, we have a fiscal responsibility to our ratepayers and taxpayers in the District to ensure that we collect these funds to maintain the health, safety, and reliability of our water and sewer systems,” says Sherri Lewis, a DC Water spokesperson, in an email to The 51st.

DC Water is now placing notices on the front door of buildings with outstanding balances, warning that water would be cut off if the bills weren’t paid within a specific period, usually two weeks.

Since March, 360 multi-unit residential buildings (most of which have eight or fewer units) received such notices, and 110 have had water shut off.

“Encouragingly, more than half of those disconnected either paid their outstanding balance or entered into a payment plan shortly after” the notices appeared, says Lewis, amounting to $1.3 million in payments.

While the exact number of individual tenants who have been affected is unclear, the impact has been skewed toward majority Black and low-income neighborhoods: 85% of the disconnections have taken place in wards 5, 7, and 8.

That the water shut-offs are hitting renters like Hoskins – who have no control over the water bill in their buildings – is what most troubles advocates and legal aid groups that are scrambling to help tenants.

“The heart of the matter is tenants are being caught between DC Water and these multi-unit landlords who didn’t pay their water bills,” says Vikram Swaruup, the executive director of Legal Aid D.C., which is representing Hoskins and other tenants in lawsuits against their landlords over the situation. “We understand that [DC Water is] owed millions of dollars. But it’s an untenable proposition that the one party who didn’t do anything wrong is the one party who is substantially harmed.”

Lewis, the DC Water spokesperson, concedes that the new policy can have a “serious impact” on renters. “When property owners – particularly those with a history of neglect – fail to pay their bills and allow arrearages to accumulate over many months, they place their tenants in a difficult and unfair position,” she says.

Advocates are also concerned that landlords could use the threat of impending water shut-offs to encourage tenants to move out.

“This whole thing is part of a trend of landlords failing to keep up their properties and treating tenants as a resource to bleed dry,” Swaruup says. “This is all a runaround to D.C.’s anti-eviction laws.”

Hoskins says that when his water was shut off, he received a letter from his landlord advising that the tenants could either collectively come together to pay the outstanding $1,500 bill or “take these remaining 30 days to move out.”

“I honestly feel like this is a ploy to push us out,” says Hoskins, who adds that one tenant did leave. (A third unit in the building was already vacant, while a fourth is currently occupied, according to Hoskins.)

Tenant advocates say the suggestion that tenants pay the outstanding water bill – which DC Water also advises – sidesteps the fact that many have been paying for water already as part of their rent.

“They're essentially being asked to double pay something in a lot of these properties in order to get the water turned back on,” says Kathy Zeisel, the director of special legal projects at the Children’s Law Center.

Michelle Washington, the owner of Hoskins’ building, says the water bill remained unpaid because she had billing questions that DC Water had not answered. She also said that her leases specify that water use is to be paid by the tenants, but that her property managers may not have billed the tenants for it. (The building has a single water meter in her name, so payment would have to come through her account.) Hoskins says he’s never been asked to pay a water bill in the two years he’s lived there.

Meanwhile, the water at Hoskins’ building was only turned on in early July after a judge ordered it, pending resolution of his lawsuit against Washington.

An additional challenge for impacted renters is that information on the new policy has been limited and scattershot.

DC Water didn’t make a public announcement, and while it has shared the addresses of impacted buildings with councilmembers’ offices, Dennis Taylor of the D.C. Office of the Tenant Advocate says his office has struggled to get similar details. “DC Water is keeping a lot of information close to its vest,” he says. (Meanwhile, Ward 8, which has seen the most water shut-offs, doesn’t currently have a councilmember.)

Advocates say that the building notices themselves can be easy to miss, so tenants may not even realize what’s coming. And the flyers provide limited and sometimes complicated information. They tell tenants they can call the attorney general’s office for help mediating conflicts with landlords, but it also says tenants can move to place their building into receivership – a complex legal process.

“It’s such an unlevel playing field,” says Ward 6 Councilmember Charles Allen, who chairs the council committee that oversees DC Water. “You’ll take a tenant who is struggling and you’ll say the only remedy is you’ll put the building in receivership. That’s kind of nuts.”

There are other resources available, but they aren’t always easy to navigate.

Hoskins called the D.C. Department of Buildings, thinking it could help. Instead, an inspector placed a bright orange sticker on his building declaring it uninhabitable. Hoskins hoped that the agency would also help him pay for a hotel, but unbeknownst to him that’s the responsibility of OTA. (Taylor says his office has helped place residents of two buildings similarly declared uninhabitable in hotels.)

Allen says that DC Water needs to do more to directly inform affected tenants. An emergency bill he unveiled on Wednesday would require DC Water to increase efforts to directly contact tenants about impending water shut-offs, while also pausing service disconnections at buildings with low unpaid balances. “If somebody’s just a month behind, that doesn’t feel like we’re at a disconnecting-level response,” he says.

Ward 5 Councilmember Zachary Parker also introduced a bill that would fully ban water shut-offs at all residential properties earlier this year, but it hasn’t moved forward in the council. He tells The 51st that he’s contemplating other solutions that would both help DC Water recover what it’s owed while protecting tenants, including having funds paid to the utility count toward rent.

For Hoskins, it’s now a waiting game. His attorney from Legal Aid D.C. has asked a judge to order DC Water to keep his water on while they try to get his landlord to pay the outstanding bill.

Standing amidst his piles of laundry, he told me that if this experience has taught him anything, it’s how much DC Water is right that “water is life.”

“Water is something I really used to take for granted,” he says. “But now I see how detrimental it is not having water and do the basics like being able to wash my body, brush my teeth, and wash my daughter’s face in the morning. It has really been a hardship.”

With your help, we pursue stories that hold leaders to account, demystify opaque city and civic processes, and celebrate the idiosyncrasies that make us proud to call D.C. home. Put simply, our mission is to make it easier — and more fun — to live in the District. Our members help keep local news free and independent for all: