With seminars and sample ballots, D.C. is teaching residents about ranked-choice voting

Election officials and community groups are targeting older and low-propensity voters with an education blitz on the new way D.C. will vote this year.

And more news from the lawmakers' final legislative meeting of the session.

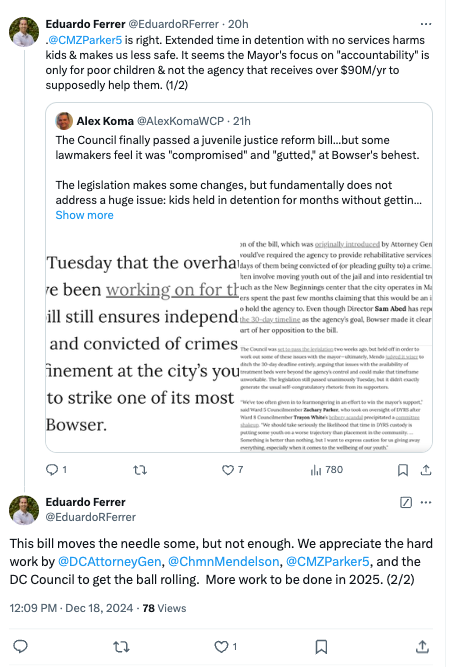

In the final legislative meeting of the year, the D.C. Council passed a weakened version of a bill meant to improve how the city’s Department of Youth Rehabilitation Services manages children committed to its care.

Lawmakers gave the bill a first vote back in November, and delayed the second vote to work out disagreements with the mayor, who voiced her opposition to the legislation. When it came to pass this week, councilmembers conceded to some of the mayor’s objections, producing an amended bill that defangs some measures meant to improve one of the city’s most beleaguered agencies.

“I am discouraged that some of the key accountability mechanisms it contains have been watered down or eliminated entirely,” said Ward 5 Councilmember Zachary Parker during Tuesday’s hearing. “And while the blame for that lies prominently with the executive, I cannot help but feel that we share some responsibility in that too … We have lost perspective on some key facts in the conversation, I think, in an effort to win over the mayor's support.”

Introduced at the request of D.C. Attorney General Brian Schwalb, the Road Act initially sought to reduce recidivism rates by requiring DYRS to make a rehabilitation plan within three days of a child entering its custody. It would’ve also allowed minors to ask the court for a case review if they had not received services within 30 days. Chairman Phil Mendelson axed those provisions in the final bill, however, ceding to opposition from Bowser.

The provisions were attempts to rectify one of the key issues at DYRS: many children wait weeks, sometimes months, for adequate placement in secured facilities. DYRS runs the Youth Services Center, a detention facility where children are held pre-trial, or while they wait for a permanent placement — either in a residential treatment center, group home, or DYRS’ other facility, New Beginnings.

But in reality, children end up at YSC well beyond 30 days, often languishing in an overcrowded detention center without individualized rehabilitative care or educational services. According to the independent monitor that oversees DYRS and its facilities, as of Thursday there were 99 children at YSC (a 98-bed facility) and the current length of stay is 77 days.

DYRS is also facing a lawsuit from the D.C. ACLU and Public Defender Service for D.C. on behalf of two teens who waited several months for services at YSC. Schwalb’s original bill would’ve imposed stricter deadlines on DYRS, and given children the ability to petition for review if they weren’t met.

Bowser expressed her disapproval to the Council ahead of their meeting.

“Enacting this bill will neither increase public safety nor will it improve outcomes for juveniles engaged in dangerous criminal activities,” Bowser wrote. “Instead, it perpetuates a revolving door at the courthouse where juveniles can commit crimes and know there’s no real accountability for their actions.”

Despite largely conceding to her wishes, Mendelson criticized the mayor’s stance, suggesting she misunderstood the purpose of the bill.

“That kind of language is very troubling to me,” he said of Bowser’s “revolving door” statement. “It creates a misunderstanding that is very damaging to the public perception of what we are doing.”

Mendelson emphasized that the bill never sought to alter criminal penalties, the evidentiary process, sentencing, or the release of children in custody.

“The bill is about requiring services for juveniles,” he said.

Several provisions of the bill remained intact, including one that requires more agency oversight, and another that allows minors to petition for case reviews every four months if they are not receiving adequate services outlined in their rehabilitation plan. A permanent oversight office for DYRS, the Office of the Independent Juvenile Justice Facilities Oversight, will exist as a permanent body within the D.C. Auditor’s office.

Another provision was added to the final bill requiring the mayor to make a plan for building a youth residential psychiatric facility for children, with the intent of alleviating the capacity strains on other residential programs that leave kids stuck at YSC.

Even so, the bill left the dais with advocates and some lawmakers sensing that an opportunity to truly overhaul DYRS had been squandered.

“Something is better than nothing but I, again, want to express caution for us giving away everything, especially when it considers the well-being of our youth,” Parker said.

Schwalb released a statement calling it a “critical and constructive step”. Eduardo Ferrer, a youth advocate and policy director of Georgetown’s Juvenile Justice Initiative, said it didn’t go far enough.

That wasn’t all the Council got up to Tuesday. Here’s some other notable legislating that happened at the end of their session. (The councilmembers will pick up their duties on the first legislative meeting of the next two-year session on Jan. 7.)

The Pets in Housing Act: The bill allows people to bring their pets into homeless shelters and limits the fees a landlord can charge a tenant for owning a pet.

Protections for incarcerated pregnant mothers: The bill guarantees specialized healthcare during and after pregnancy and allows an individual to request the presence of another person to support them during labor.

Ending child marriage: (Yes, that was still legal!) The bill raises the age requirement for a marriage license from 17 to 18, bringing D.C. in line with most of its northeast counterparts, like Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, New York, New Jersey, and Delaware.

Cracking down on fake tags: New legislation revamps D.C.’s parking enforcement penalties, making it easier to tow cars with fake tags.

Streateries can stay: A bill from Councilmember McDuffie extends the city’s streatery program through next July.

Big money for Cap One Arena: Lawmakers finalized a $515 million deal to renovate Capital One Arena.

With your help, we pursue stories that hold leaders to account, demystify opaque city and civic processes, and celebrate the idiosyncrasies that make us proud to call D.C. home. Put simply, our mission is to make it easier — and more fun — to live in the District. Our members help keep local news free and independent for all: