Go ahead and file your taxes, says D.C. CFO amidst confusing fight over tax law

No pause or delayed deadlines are now expected.

The history of D.C.'s official dance.

On a Monday afternoon at Roots Public Charter School in Northwest D.C, students in kindergarten, first grade, and second grade stood facing each other — boys on one side and girls on the other. Holding hands with their partner, they counted out the beats to their steps: one and two, three and four, five and six.

On three and four, their hands released, and the girls twirled in a circle.

“Beautiful,” said instructor Kevin Fitzhugh. “You know why it’s beautiful? You did it together as a team. Everyone turned on three.”

What makes this lesson particularly unique is that they’re tracing the steps that generations of Washingtonians took before them. This dance first took root in the District’s house parties and streets of the 1950s, and over the course of 75 years, it has cemented itself in the city’s cultural history.

It’s called hand dance, and it’s D.C.’s official dance. Now, a tight-knit community is doing what they can to help it stay alive.

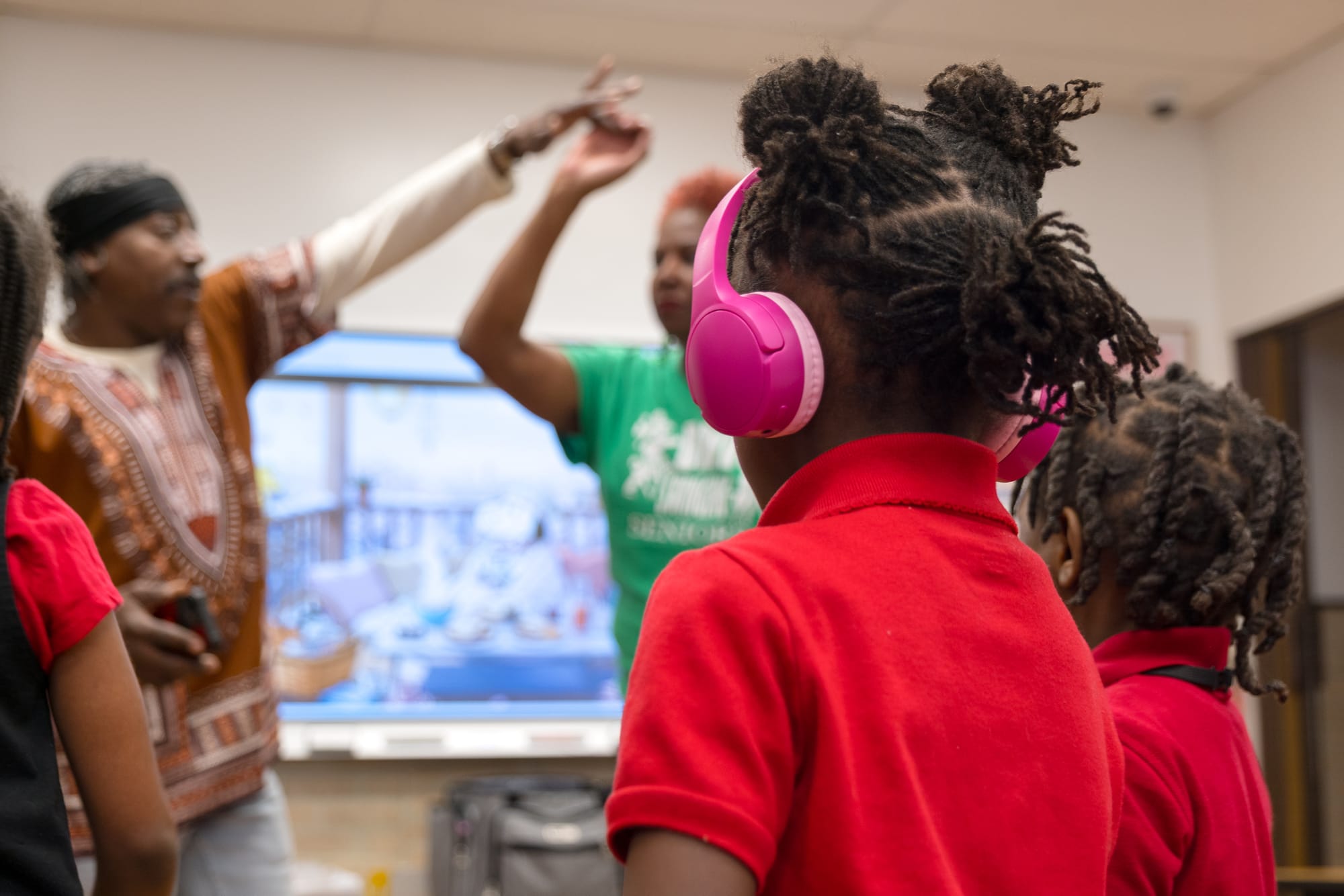

Kevin Fitzhugh and Kim Frazier teach hand dancing to Roots Public Charter School students in Northwest D.C. (Shedrick Pelt)

In the 1920s and 1930s, swing was king — and nowhere else was that more true than the Savoy Ballroom in New York City’s Harlem. It took up an entire block and hosted jazz legends like D.C.’s Duke Ellington, Baltimore’s Chick Webb, and famous singer Cab Calloway. It was also one of the few racially integrated dance halls at the time, a place where Black and white dancers could come together.

The Lindy Hop, a high-energy partner dance, took off at the Savoy. Rooted in the Black communities of Harlem, it’s often recognized as the original swing dance. It inspired and shaped other forms of swing across the country, including hand dancing in D.C.

“People went [to the Savoy] to experience it, learn it, and bring it back,” said Kim Frazier, author of D.C. Hand Dance: Capitol City Swing and one of Roots’ hand dance instructors.

Each of these regional dances, like the Philly bop and the Chicago step, took on “the nuances and flavors of the community,” said Beverly Lindsay-Johnson, a hand dance historian and humanities scholar.

Hand dance (originally known as “fast dance”) cemented itself in D.C. during the 1950s and 1960s. It was closely attached to specific styles of music, particularly Motown, and artists like The Supremes, Marvin Gaye, and The Temptations were staple choices.

For young people at the time, hand dance was everywhere. “You learned it through your community, your siblings, your classmates,” said Lindsay-Johnson. “You had sock hops, you had rec centers, you had block parties, you had basement parties, you had backyard parties.”

Frazier’s earliest hand dancing memories are at her mom’s basement parties in Northwest D.C. “We would sit on the stairs and just peep to see what was going on with the adults. My mother and her brother were dancing, holding hands, hopping around the basement,” she recalled. “I said, ‘I want to know what that is. I want to learn that.’”

Hand dance had its own dialects — people could occasionally tell what quadrant of the city someone came from, depending on their dance style. Different forms emerged, too, like the bop, which is a slower version of hand dancing, and the skate, which pairs with up-tempo music and features gliding and sliding.

Hand dance also differed between the District’s deeply divided Black and white communities. While restaurant segregation was outlawed in D.C. in 1953, followed by school integration in 1954, segregation persisted in practice thanks in part to federal control of the city and to many white communities' dogged efforts to resist change.

“There was no commonplace where we could exchange steps and dance and learn from each other,” said Frazier.

The city’s dance culture reflected these fights. The Milt Grant Show, a popular teen dancing program local to Washington that started in 1956 only allowed Black teens on the show one day a week, with the rest dedicated to white youth.

By 1963, a Black dance program was launched in D.C. called Teenarama, and it was more than just a show where Black teens could hand dance together. “It gave the teens a sense of themselves and what they could do — that they were just as good at dancing,” said Lindsay-Johnson, who produced two documentaries on the impacts of Teenarama.

After Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in 1968, riots erupted around the country, including D.C. Over just four days, 13 people died, over 900 businesses were damaged, and over 7,000 Washingtonians were arrested. It became much more difficult to travel to the show, and parents of Teenarama dancers worried for their children’s safety.

Despite the turmoil, Teenarama stayed on, providing details for their dancers on how to get to the show safely. During this time, it became a safe haven where young Black Washingtonians could dress up, hand dance, and enjoy themselves on television — when the media rarely portrayed them in a positive light.

Teenarama was on air until 1970, and as the District entered the decade, hand dance saw a period of decline as disco music came to the forefront.

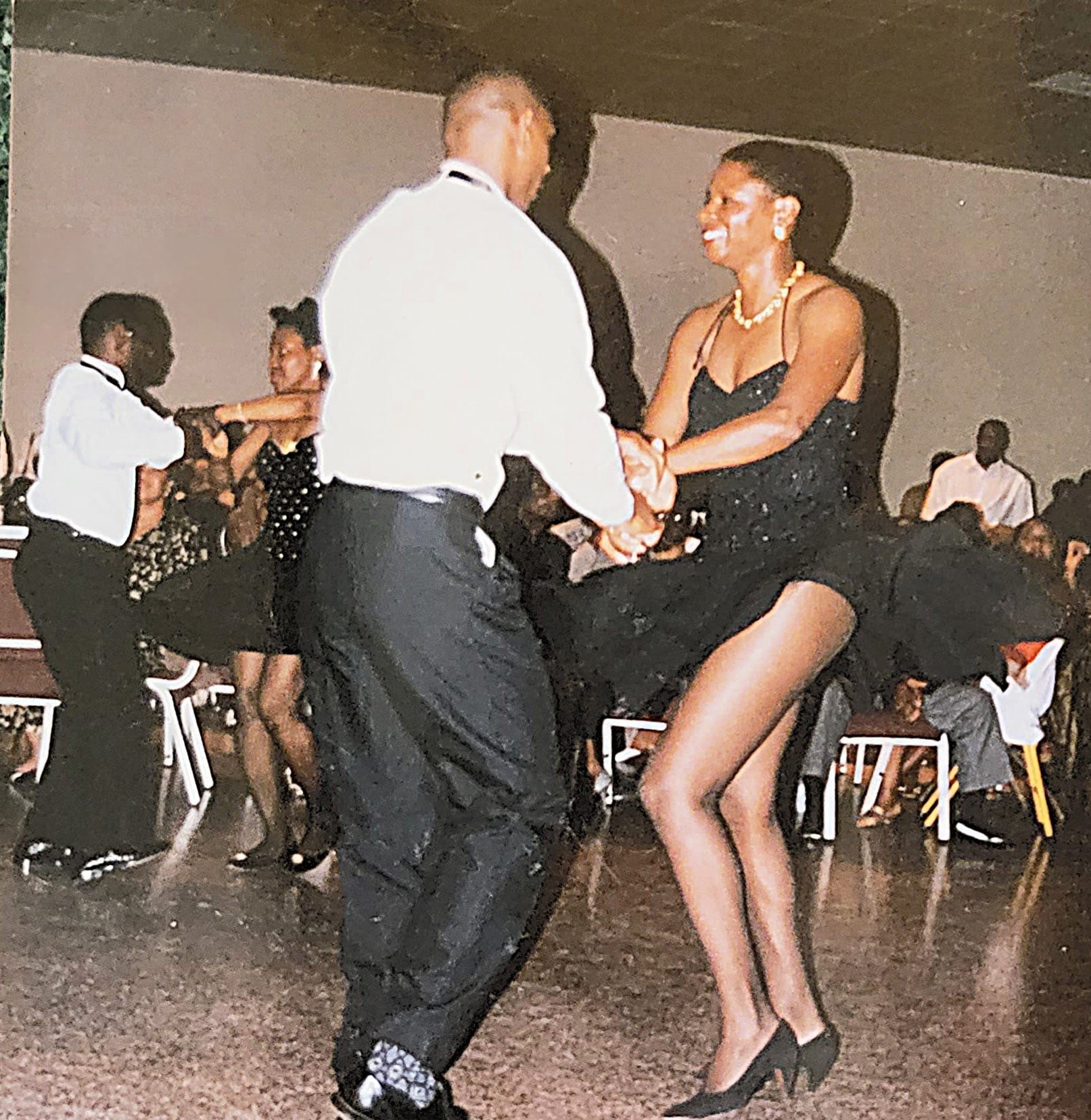

Left: Kim Frazier and her dance partner perform with a synchronized hand dance team in the mid-1990s. (Courtesy of Kim Frazier) Right: A portrait of Kim Frazier. (Shedrick Pelt)

In the early '90s, a young man named Steve Mitchell made his first visit to The Solar Eclipse, one of the few venues where hand dancers still came together. While the dance had fallen out of favor in the previous decades, swing was experiencing a cultural resurgence, according to Frazier, fueled by media like the Gap Lindy Hop commercials and the 1992 film Malcolm X.

Mitchell remembers being mesmerized by one hand dancer at first. But then someone pointed him in the direction of Lawrence Bradford on the other side of the dance floor.

If the first hand dancer was like a high school star basketball player, Mitchell said, then Bradford was like Michael Jordan. “I knew where I was to be,” Mitchell said of that moment.

Bradford, a native Washingtonian, was a key figure in hand dancing’s resurgence in the 1990s. He taught classes at the Eclipse and people like Mitchell, enthralled by his moves, eagerly signed up.

For Lindsay-Johnson, the magic of hand dance was less about the moves and more about the people. During her first time at the Eclipse, she quickly realized that the overwhelming majority of people in the club were deeply familiar with each other.

“You could see the love and camaraderie of people within the dance,” said Lindsay-Johnson. It helped her understand D.C. as a city that, at the time, was a place where people’s families stayed for generations. That moment introduced her to hand dance, and started her journey to becoming a historian.

“I said, ‘This is more than just a dance,” Lindsay-Johnson added. “This is a culture.’”

Like all culture, it was often contested. In his classes at the Eclipse, Bradford (who was called “Brad” or “Mr. Brad” by his students) was teaching a novel style of hand dance. Eventually, he found a name for it: smooth and easy, which would inspire the name for his school of dance, the Smooth and EZ Dance Institute.

But not everyone was on board with Bradford’s new school version. Some of those who learned the old school way — in their communities, with a focus on foot work and an attachment to music of the 1950s and 1960s, for instance — much preferred their style. The variations arose for a variety of reasons: new music, a different venue for learning, and also a changing culture.

“Dance reflects life,” Bradford said in an oral history interview with the D.C. Public Library about hand dancing. Like other swing dances, hand dance has a leader and a follower. Typically, the leader is a man and the follower is a woman. In his interview, Bradford told a story about a man who walked off the dance floor after his partner took a double turn when he wanted her to turn only once.

“In his mind, he was in charge. And in the '50s and '60s, he was flat out in charge. No ifs, ands, or buts about that,” he said. “Today in the house, he ain't in charge. It’s shared.”

As Bradford’s classes fueled a renewed interest, other organizations were also established to promote it, like the National Hand Dance Association, which helped start local hand dance competitions.

Many Smooth and EZ graduates, like Frazier, Mitchell, and Fitzhugh competed in the District, Maryland, Virginia, and even as far as California. They danced among the best, showed off D.C. hand dance, and very often won their events.

By 1999, the D.C. council recognized hand dance as the official dance of the city.

The youngest generation of Bradford’s students includes Tia Quander and Randy Portis, who remember sitting on the floor of the Eclipse together as Quander’s grandmother and Portis’ mom took lessons at the Smooth and EZ Institute. It wasn’t long before both of them were roped into Saturday hand dance youth classes.

During the adult classes, the two would join other kids in a back room at the Eclipse and practice elaborate dance moves ahead of their weekend classes. “We’d have so much fun in the back room that we wouldn't even know that the classes were over,” said Portis. “The parents would have to come and drag us out the back room.”

Now in their early 30s, the two have been each other’s dance partners since they were teenagers. But there aren’t many others like them, and even more rare are hand dancers younger than them.

When Bradford passed away a few years ago at the age of 78, the city lost one of its biggest advocates for hand dance. In the month leading up to his death, he was still teaching. Charles Matthews was one of his last students. Though he had grown up seeing friends like Mitchell hand dance, it wasn’t until later in life that he decided to take classes.

“I just never had an opportunity to thank him,” said Matthews about Bradford. “So I said, ‘Well, what I'll do is thank the community that he helped cultivate.’”

That led Matthews to start Black Hand Dance Excellence, which gives out dance scholarships to community members and hosts an annual gala. At this year’s gala, they’ll award over a dozen of the city’s best hand dancers for their different contributions to preserving the dance. Quander, Portis, and Lindsay-Johnson are among this years’ honorees.

While hand dance enjoyed a period of revitalization, there are now no hand dance classes for the public in D.C. Most classes today are just outside the city, in Maryland suburbs.

The Chateau Lounge is also the only local venue that still offers hand dance events in the District, after the Eclipse closed in 2014. And the loss of Bradford also meant the loss of an iconic instructor for an entire city.

For Quander and Portis, who spent countless hours with him in classes and competitions, Bradford was more than just a teacher. “Mr. Brad was family,” said Quander. “It was beyond hand dancing with him.”

For many people, that sense of kinship is what keeps them coming back to the dance. When Black Hand Dance Excellence interviewed D.C. hand dancers about what made them fall in love with the dance, one answer consistently came up. “The common denominator is always the community, and how it makes them feel,” said Matthews.

“Being able to share time together, laugh together, dance together, have fun together,” he added. “That's what the dance brings. It brings community.”

In his interview with the DCPL, the one thing Bradford wanted others to take away from his legacy was to keep promoting the dance.

“One of the things that we should learn, that history should teach us, is if we don’t do that it might go away,” said Bradford.

Left: Kevin Fitzhugh and Kim Frazier demonstrate a turn for the Roots Public Charter School students. (Shedrick Pelt) Right: People attending a 2025 hand dance day party at the Elks Lodge in Temple Hills, Maryland. (Charles Matthews)

Back at Roots Public Charter School, it was time for students to try it out with the music.

“Stand By Me” by Ben E. King filled the room. This time, the tempo is a little too quick for some of the kids, and it’s back to practicing with no music. One boy exclaimed after, “That was so fast!”

The students are practicing for their annual end-of-the-year recital. At this age, the kids don’t always have the longest attention spans. In between learning steps, there are side conversations and bursts of giggles. But as the class goes on, the kids get better at picking up the moves of their city’s official dance.

“They have a lot of energy,” said Frazier. “But when you see the final performance — we’re blown away sometimes.”

This story has been updated to reflect Beverly Lindsay-Johnson's introduction to hand dance and to reflect the correct year the Milt Grant Show started. The resources guide has been updated to reflect the producers of two of the documentaries.

With your help, we pursue stories that hold leaders to account, demystify opaque city and civic processes, and celebrate the idiosyncrasies that make us proud to call D.C. home. Put simply, our mission is to make it easier — and more fun — to live in the District. Our members help keep local news free and independent for all: