Baby steps: Janeese Lewis George pledges universal affordable child care for D.C.

It’s not free, and her plan faces fiscal challenges.

Tree of heaven, also a non-native invasive organism growing around D.C, is their favorite meal.

You know the drill: You see one, you step on it. Or smoosh, squash, smush.

Nearly a decade after a spotted lanternfly was first found in Berks County, Pennsylvania, the invasive species has become public enemy number one. State-sanctioned “stomp it out!” campaigns have people committing bug murder on-sight as though it’s their civic duty, akin to recycling a yogurt container or voting in a local election.

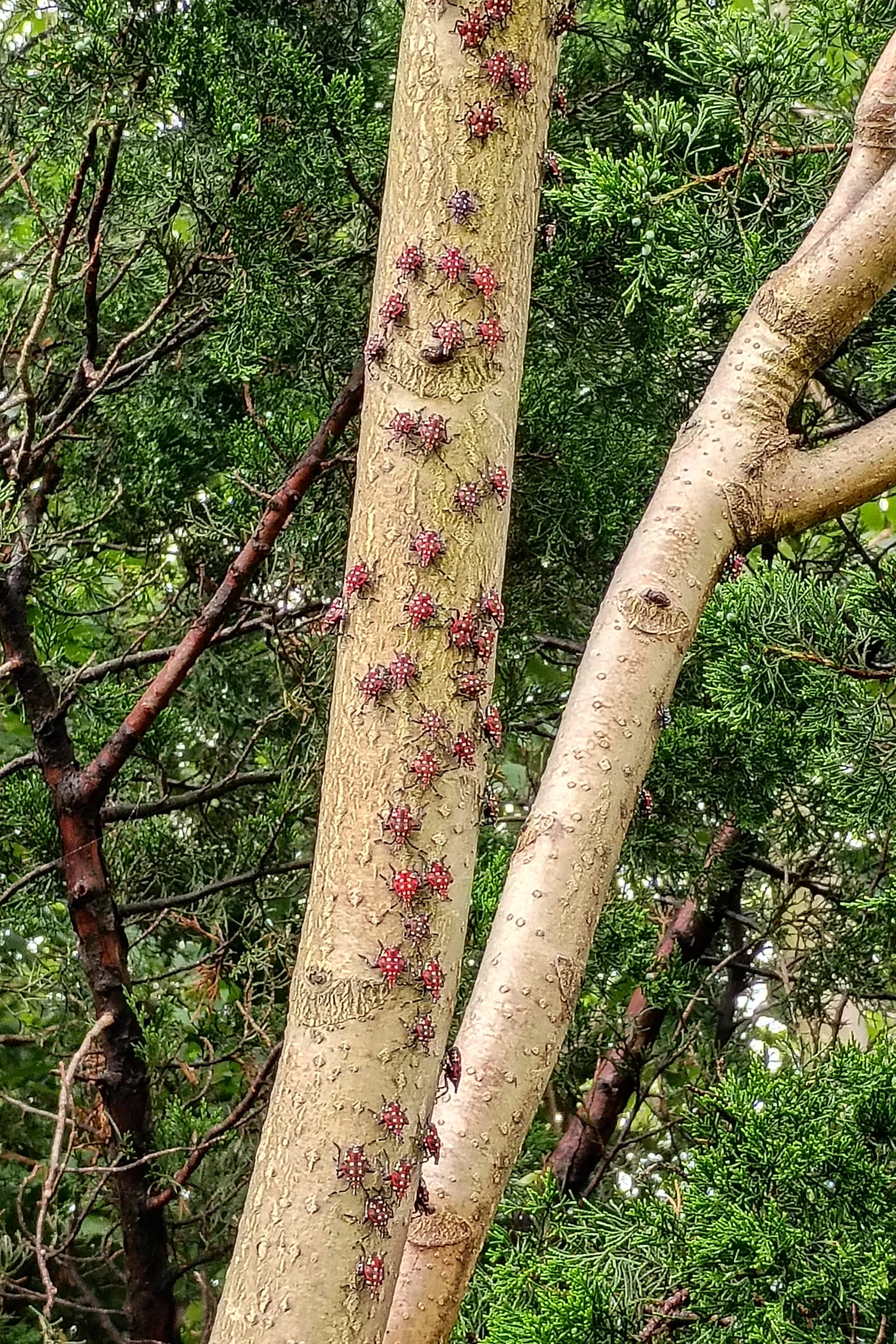

But as the insect continues its spread – evidenced by a banner egg-laying season in D.C., according to local biologists – it’s clear that puny human efforts to eradicate the polka-dotted creatures aren't doing much. In a classic tale of man versus nature, nature appears to be winning.

“I see them all over the place,” says Damien Ossi, a wildlife biologist with the D.C. Department of Energy and the Environment, noting that the population of nymphs is much bigger than last year’s. “It's kind of surprising … how many adults we're going to see this year.”

Once they’re here, they’re here. They’ve become a part of the landscape in states from New Jersey to Virginia, where officials’ mission is one of management rather than eradication. But in D.C., there’s another invasive organism aiding the species' rise to power: the tree of heaven, or Ailanthus altissima. Known for its stubbornness, it’s a tree that grows pretty much anywhere the wind blows it – literally — and a favored host of the spotted lanternfly.

“The tree of heaven population in the District is growing, and it has been growing mostly because of its biology — I mean, it produces a lot of seeds and they're wind-blown seeds,” Ossi says. “It’s an incredibly hard tree to manage.”

While spotted lanternflies don’t need the tree to reproduce, they’re seven times more productive if they have a heavenly host. As Michigan State University researchers put it, this is a “tale of two invaders.”

So what are we average citizens supposed to do about this? What is our city doing about it? And are all of these efforts for naught?

Originally from Asia, the spotted lanternfly feasts on the sugary sap of trees. Inside their mouths, they have what Georgetown biology professor Martha Weiss likens to a hypodermic needle. They stick their tiny mouth-straw deep into the “phloem” tubes of the tree, where the fluid is much sweeter than the “xylem” tissue near the roots, and take big swigs. (Cicadas, a less destructive “cousin” of spotted lanternflies, are xylem-feeders, and use their straws to drink from the tissue in the roots and stems of a tree.)

Aside from the tree of heaven, spotted lanternflies will get their fill from maples, willows, and birches. They’re also particularly drawn to grapevines, causing headaches for winegrowers and other agricultural producers in rural areas.

The flies’ sweet tooth creates excrement called honeydew, which you might see on the sidewalk or car windshields. It’s a sticky, sugary poop that coats surfaces in a black sooty mold, attracting bees, ants, and various forms of fungi.

We’re told to murder lanternflies on sight because the bugs — and their poop — can wreak costly havoc on crops. But in an urban environment like D.C., the bugs will be more of a pest — covering patio furniture in their moldy secretions or buzzing around your picnic – than an existential threat to our ecosystem, according to Ossi.

“They're more of a nuisance to people and their property,” he says. “They won't really disrupt the natural ecosystem.”

And you can get to stomping all you want, but it’s a bit like draining a swimming pool one cup at a time. Weiss says “my feeling is, if they have arrived in an area, then squishing them is not going to make that big of a difference, because there's going to be thousands more where that one came from.”

Instead, keep an eye out for their egg masses. In the fall, adult flies lay eggs in waxy clumps on a tree. They’ll stay cocooned until hatching into black-dotted larvae in the spring. These “nymphs” then turn red in late spring and early summer, before maturing into the gorgeous/menacing adults we’re used to seeing around July.

Because the nymphs are so good at jumping around, you’ll be hard pressed to squish them. Ossi says it’s best to get a vacuum and suck them up if you spot the larvae in your yard. (You can also report nymph and adult sightings to D.C.’s Department of Urban Forestry.)

Ali Schneiderman, the coordinator for the University of the District of Columbia’s Master Gardener Program, says some people have also made traps for their backyards by wrapping sticky paper around the base of a feeder tree. (You can then put the paper in a bag with some alcohol to kill the bugs.)

While she’s seen more nymphs in D.C. than in previous years, Schneiderman says they’re not posing much of a threat to local gardeners. They really only kill grapevines and maple saplings; in your backyard, they may just weaken already unhealthy plants. She advises watering the plants you care about really well so they’re stronger and better able to defend themselves.

From left to right: early stage nymphs, late stage nymphs, adult spotted lanternflies. (Damien Ossi)

No matter how much we suck and squash, the real battle against spotted lanternflies might be waged on the tree of heaven. And it’s a fight D.C. (and most urban areas) has lost time and time again.

The story of how the tree, native to China and Taiwan, ended up in the Mid-Atlantic is (you can probably guess) one of colonialism. Western landscape designers were fascinated by the “exotic” gardens of Asia and brought the tree over to Europe and later colonial America for ornamental purposes in the 18th century. By the 1800s, urban planners were planting the tree across Northeast cities, both for its looks and its resiliency to pollution and urbanization – it could grow even in the crappiest of soils. Of course, it was this same resiliency (and the funky smell) that eventually made it a nuisance to urban foresters. Congress put a stop to all tree of heaven planting in D.C. in 1853, and landscape architects began calling it a “usurper” of the natural environment. (You make a bed…)

More than 150 years later, we’re still dealing with the plant. It’s less common in undisturbed forest areas like Rock Creek, and instead thrives in alleys and sidewalks, according to Ossi. Like maple trees, tree of heaven seeds spread through flying-saucer-looking leaves, and they can grow pretty much wherever they land: cracks in the sidewalk, along roadways, at the base of a fence, and, unfortunately, our backyards. (Ossi says the tree is so plucky, it’s even grown out of a crack in the Great Wall of China!)

“It takes advantage of these disturbed areas — even a little crack in the cement, if the seed gets there, it’ll grow,” Ossi says, adding that the city is currently working to address a large mass of the trees along Suitland Parkway.

Aside from hosting spotted lanternflies, the plants (which can grow up to 80-feet tall!) also secrete chemicals that prevent other, native plants from growing and germinating, disrupting our natural ecosystem.

To identify tree of heaven, look for smooth oval leaves with a sharp point, and give them a sniff. Tree of heaven has a curious odor that’s been compared to spoiled peanut butter or Cheerios.

But removing it is difficult thanks to an extensive root system, which spreads wide rather than deep. If you cut down one seedling, the root system is likely to just sprout up another one somewhere else.

“Pretty much the only way you can kill it is either to dig it completely out or use an herbicide,” Ossi says.

DOEE and D.C. Department of Urban Forestry officials don’t endorse the use of herbicides and insecticides for invasive species control, though Ossi notes that spraying an exposed surface of a tree of heaven stump could be enough to kill it, should a resident choose that route. Instead, city efforts largely focus on digging up mass growths. If you do spot one, you can report it to D.C.’s Urban Forestry Department.

Left: Tree of heaven leaves. (Martha Weiss). Right: Overgrown tree of heaven. (David Berry/Flickr)

The language around tree of heaven and spotted lanternflies is dramatic and militaristic; we’re enlisted to kill the “non-native” “invaders.” But Ossi and Weiss both say the best advice in this seemingly never-ending mission is to remember that, at the end of the day, we’ll probably be okay.

“I don't think we need more fear-mongering of bugs that are going to hurt us,” says Weiss, who in speaking to The 51st, admitted that as an entomologist, she approaches these things with a particular bias. “We don't necessarily want them in our backyards or our urban parks – in part because they do disrupt ecosystem processes and because the honeydew can be a mess — but they're not going to bite us, they're not going to sting us. They're not like mosquitoes or ticks that can give us diseases.”

Ossi says that the first thing he tells people when they encounter spotted lanternflies and tree of heaven is: don’t panic. Remove any eggs you see, and sure, give a stomp. But we may just have to put up with the pests for a while.

Ongoing research suggests that in areas where the spotted lanternflies first landed, nature itself may be stepping in to do some population control. Predators like birds and bugs are adapting to their presence in the ecosystem and learning to like their taste, the longer the spotted lanternflies feed on the local ecology.

“What has been seen over the course of the last couple of years up in Pennsylvania and places where they've been for almost a decade now, is that the more they feed on other species of plants, they’re more palatable,” Ossi says. “Predators start to recognize them as a prey item, and the populations eventually get reduced again, mostly by natural predation.”

So we may be up against a buggy few months, but it won’t be the end of the world. While we tempted fate with the tree of heaven centuries ago, this time, we may have to let nature do its thing.

With your help, we pursue stories that hold leaders to account, demystify opaque city and civic processes, and celebrate the idiosyncrasies that make us proud to call D.C. home. Put simply, our mission is to make it easier — and more fun — to live in the District. Our members help keep local news free and independent for all: