Wilson Building Bulletin: A cold dose of reality on D.C.’s budget

And Trayon White gets a new trial date.

Once a symbol of defiance, the mural now exemplifies the mayor’s shift in approach to an aggressive GOP.

It was a quiet hint, but a telling one.

Shortly after President Trump was elected last year, Mayor Muriel Bowser was asked by NBC 4 reporter Mark Segraves whether she would consider removing Black Lives Matter Plaza — the large art installation stretching three blocks along 16th Street NW just north of the White House — if Trump asked her to. Bowser, who created the plaza as a symbol of resistance to the first Trump administration in 2020, demurred.

And on Tuesday afternoon, Bowser jumped ahead of any official presidential request and made the announcement herself: Black Lives Matter Plaza would soon be no more. The mayor's decision came a day after Rep. Andrew Clyde (R-Georgia) introduced a bill calling on D.C. to paint over the plaza and rename it “Liberty Plaza" — or risk losing half of the $270 million in federal highway funds it receives on a yearly basis. Republicans made a similar request in late 2023.

“The mural inspired millions of people and helped our city through a very painful period, but now we can’t afford to be distracted by meaningless congressional interference,” Bowser said in a statement, adding that it would be replaced by a mural linked to the celebration of America’s 250th birthday. It's not clear when the mural will be replaced.

Clyde's bill is part of a broader message Republicans have been sending D.C. since they took control in January: We can take over the city, if we want to.

And they could. As we’ve written here before, D.C. has limited home rule — and plenty of Republicans who would love to repeal it. Trump himself has repeatedly groused about crime, homelessness, and graffiti in D.C. and mused about taking control of the city. But even if he doesn’t go that far, Trump and congressional Republicans still have various levers at their disposal to dictate what D.C.’s elected officials can and can’t do.

Bowser, now in her third term, has shown she is extremely aware of that. Unlike during Trump’s first term, when she was more aggressive in pushing back against him, this time around she has adopted a much more cautious approach. She has spoken about finding common ground with Trump on getting more federal workers back to the office (before he started pushing to fire as many of them as possible), and encouraging the federal government to turn over more of its underutilized properties for private redevelopment (which could now even include some of the city’s larger federal buildings).

In her statement on Tuesday, she continued to push that message. “The devastating impacts of the federal job cuts must be our number one concern,” she said. “Our focus is on economic growth, public safety, and supporting our residents affected by these cuts.” In short: There are bigger fish to fry than the plaza.

For some who agree with Bowser, it’s simple pragmatism. “I think it’s a pretty sensible decision,” Keyonna Jones told The 51st. She was one of the seven artists who helped paint the 35-foot-tall yellow letters on the roadway. “There’s a lot of things that need to take priority: a lot of people losing their jobs, a lot of resources the city may lose.”

But for some of her critics, Bowser’s decision on the plaza represents a preemptive surrender to Trump. “One of the things we talk about a lot in our organizing is the importance of not obeying in advance,” wrote the Free DC Project – which has been organizing to fight back against Republican attempts to interfere in local affairs – after Bowser’s announcement. “History teaches us that authoritarian leaders will use intimidation and fear to try to get people to obey in advance, because it's just a lot easier than forcing people to comply.”

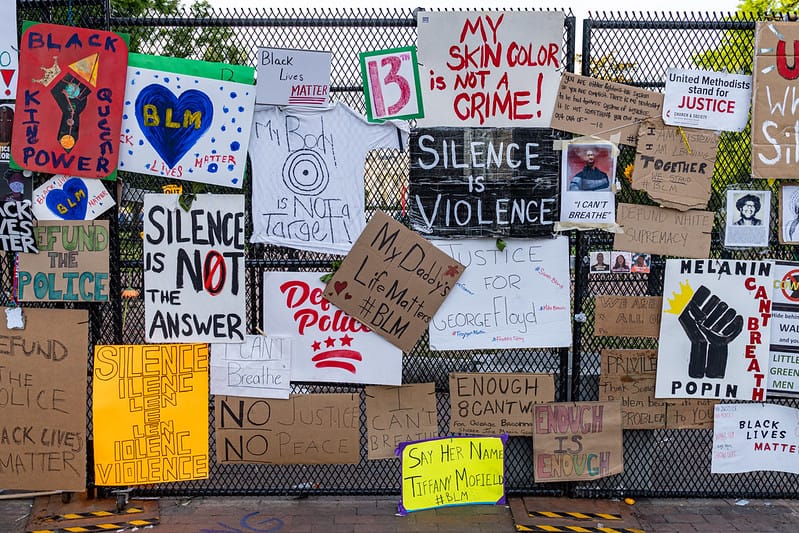

Those feelings are only heightened by the symbolism of Black Lives Matter Plaza. Stealthily created by artists commissioned by D.C. in the wake of racial justice protests following the murder of George Floyd in the summer of 2020, the plaza was meant both as a call for justice and a challenge to Trump’s heavy-handed response to protests across the country, but especially in D.C.

“We want to call attention today to making sure our nation is more fair and more just and that Black lives and Black humanity matter in our nation,” said Bowser on the day she officially christened the public art project “Black Lives Matter Plaza,” a name the D.C. Council later enshrined in law.

But the plaza was also more than that: It was also a call for D.C. statehood.

“For decades, racist accusations about District residents not being able to govern ourselves were used to deny us the rights that every other taxpaying American is guaranteed by the Constitution. Still today, without any senators and with no vote in Congress, we are denied full access to our nation’s democracy,” Bowser wrote in an op-ed in The Washington Post shortly after the paint dried on 16th Street. “The story of Washington is a civil rights story — of an entire city that, for decades, functioned as an agency of the federal government, a federal government that imposed segregation and denied proper resources to residents they weren’t accountable to.”

The plaza made Bowser a national symbol of resistance to Trump, so much so that it served as a prominent backdrop when she gave a televised speech to the 2020 Democratic National Convention. John Lewis, the late civil rights icon, visited the plaza with Bowser in tow.

Still, the narrative around Black Lives Matter Plaza was never that simple. Local activists accused Bowser of hijacking the cause for her own purposes. This week, local activist Dana White said the mayor created the plaza to “pacify protestors and as a personal flex to Trump in his first term. She then leveraged that to win re-election and has continued to push harmful policy that targets Black people in D.C.” That echoes an argument from the local chapter of the Black Lives Matter that the street mural was “performative.”

And so, too, may be the decision to preemptively paint over the plaza; or, as Bowser cryptically referred to it in her statement this week, kick off “Black Lives Matter Plaza’s evolution.” Evolve it might, but the underlying conditions that birthed it won’t. The plaza was partly created as a symbol of D.C.’s fight for self-determination, and it could be erased just as that self-determination faces more serious threats than in any time since the city gained an elected government.

“We are subject to the whims of the federal government. Sometimes they are benevolent and sometimes they are not,” Bowser said back when the plaza was created five years ago. She seems to be hoping that removing paint will garner benevolence.

And maybe it has – for now. On Wednesday, The Washington Post reported that the White House has seemingly backed off a threat to issue an executive order that could have impinged on the city’s local affairs. (It’s unclear whether the plaza decision factored into that.)

For Keyonna Jones, even if the paint is removed from the roadway, the message doesn’t have to be. “It’s a time in history that can’t be taken away,” she told us. “That’s the great thing about art. You can always create again.”

With your help, we pursue stories that hold leaders to account, demystify opaque city and civic processes, and celebrate the idiosyncrasies that make us proud to call D.C. home. Put simply, our mission is to make it easier — and more fun — to live in the District. Our members help keep local news free and independent for all: