Two years since DCist was shut down

Plus, a chance to double your support to The 51st (more on that below)

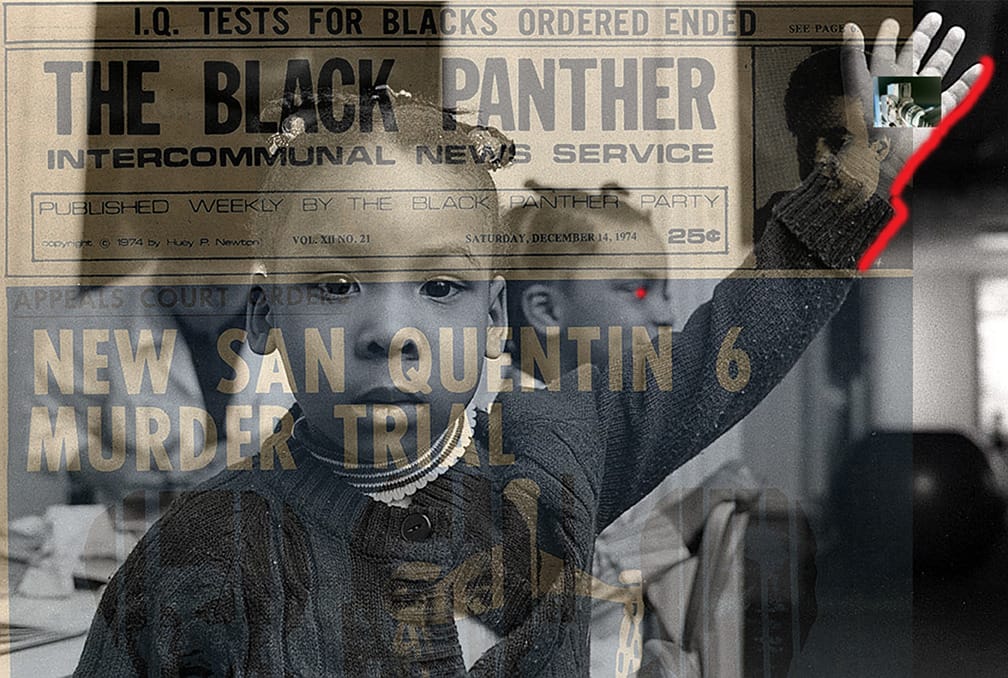

The artist and activist has been photographing an ever-changing city for more than six decades.

Leigh H. Mosley carries many titles: photographer, videographer, filmmaker, activist, educator. Her six decades of work form an intimate record of D.C.'s ever-shifting community. Born here but raised just blocks from where Malcolm X once lived in Roxbury, Massachusetts, Mosley now lives and works mere blocks from Meridian Hill Park, otherwise known as Malcolm X Park. From her home, she can hear the drummers who have gathered there for sixty years in his honor.

In a striking synchronicity, Mosley returned to D.C. in 1965, the very year the drum circles began, to attend Howard University. The city has spoken to her from the beginning: “I've always felt comfortable here. Always. Even now,” she says.

Her childhood in Boston, however, offered a sharp contrast. Stepping outside her neighborhood often meant confronting open hostility, which shaped a drive to fight injustice. “When I was young, I was a revolutionary and I was getting ready for the revolution,” she recalls. “I thought that we were gonna fight this battle, but I didn't realize that the battle was multilayered.”

Over the decades in D.C., she’s been exploring the work that goes into political change. Her Columbia Heights studio, perched atop a Victorian townhouse, is lined with an extensive library: Pedagogy of the Oppressed, The Philosophy and Opinions of Marcus Garvey, and other worn spines that testify to the depth of her curiosity and political convictions. Cameras and lenses rest in nearly every corner, everything neat and ready for use.

Photo refers to light and graphy to drawing or writing in Greek. “I feel that I've inherited this thing to write with light. I am a light bearer,” she says.

Mosley herself is both practical and stylish. Her speckled black, white, and neon glasses perch at the bridge of her nose, hinting at her whimsy. Her hair is pulled into a relaxed bun, edges smoothed; her complexion is clear and soft. Traces of her eighty years are nearly undetectable. At a carnival's guess-your-age booth, she'd walk away with an armful of prizes.

Her demeanor is calm, resolute. Conversation moves easily, ideas come quickly, and aspirations overflow. She creates when the feeling hits, trusting that whatever emerges is rooted in commitment: to herself, to her community, and to the uplift of humanity.

Her latest documentary is Pioneers for Justice: Black Lesbians in the DMV, featuring interviews with longtime organizers. Ahead of its release next year, we sat down to discuss the expansiveness of her work and life, as well as D.C. as a home, sanctuary, and creative ground.

Below is a transcript of our conversation, edited for length and clarity.

You’ve been photographing D.C. for decades. What has kept you inspired to stay here all these years?

D.C. is the Black Mecca. At least, it was when I got here. I used to visit from Boston and go to the Howard Theater. I saw James Brown on stage and all these Black people just walking around in the streets. Being surrounded by other people like me, I was just so, so happy. One of the things that’s inspired me is that there's still a base here for Black people, of Black life. There’s a spirit here that I still feel. There's still this essence.

I connect with a lot of people who live here too — with native Washingtonians. I'm just interested in our life, how we live, how we struggle, how we create, how we do things to make ourselves happy, even in the face of discrimination and oppression. We have this thing where we are going to live, we are going to thrive, no matter what.

Photography can be both art and activism. Do you see your work as part of D.C.’s cultural preservation or social commentary — or both?

Both. I've been documenting a lot of activities that people have been involved in and personalities.

One of my favorites was Marion Barry. I used to love to photograph him. He was such a character. He put himself on the line for the Black community — for the poor Black community. If you ever listen to politicians talk, mostly they talk about the middle class … but very seldom do you hear anybody talk about poor people. Especially poor Black people. And he did.

He also showed up for women's rights. He used to come to stuff for gay pride. He used to come to the Black women's table at Black Pride called Sapphire Sapphos. You know, he would just show up and be supportive.

How has being part of the LGBTQ+ community informed your work?

Well, first of all, I'm a Black lesbian, and I have to take into consideration the time I'm living in, the people I'm photographing and whether I'm being invited to capture them. I always try to be sensitive towards people in general. I never like to feel that I'm being invasive.

I feel that I've passed on a legacy in terms of things that I've documented, particularly the first National Conference of Third World Lesbians and Gays that was held at Harambee House in 1979. That was a real biggie. It was the first big gay pride march and I was there with my camera — my eye documenting a piece of history that I don't think should be forgotten.

Tell me about your latest project — the documentary featuring interviews with local Black lesbians over 70.

These eleven women have made substantial contributions to D.C.’s LGBTQ+ and the Black communities over the last 40 to 50 years. It means quite a lot to me and to other people, too.

I've been here for a while and I have gone through various phases of the Black power movement, the women's movement, the LGBTQ+ movements. These people have opinions that speak to my own thoughts and feelings.

Who is the film speaking to?

Essentially, the Black, lesbian, gay, and transgender community — but on a broader scale, anybody that will look and listen. Because hopefully, people will hear some stuff that’s a wake-up call.

One person in the film developed this place called Mary's House, which is a place for older Black gay people to live in Southeast Washington. One of the things she talks about is the oppression of being a Black lesbian who is older, who has to keep struggling to be heard. You know, 'cause people just shut you down.

What is the responsibility of an artist?

All artists, especially writers and visual artists, have a vision and a gift. And we have a responsibility to evaluate what's going on and give people some kind of feedback, in whatever form that we need to do that. I used to get into fights with a painter that lived here in D.C. because he would say that his work is revolutionary. I would say, your work is wonderful, but it's not revolutionary. It wasn't doing anything to move Black people or enlightening us in any way.

How has living in D.C. contributed to your understanding of yourself and your politics?

I mean everything is political. All of your choices. What we choose to eat, what clothes we're gonna wear. Do we notice who made those clothes and who those people were? What's behind that? What are we doing for entertainment? What are we doing for education?

How do we interact with people? How do we feel about ourselves? 'Cause it all comes down to numero uno. If you can't get down with yourself and be reasonably pleased with the person that you are and to the outside world that you have to function in, then that's a problem.

How personal is your work to you?

Everything's personal. It’s personal and political. It comes from me, from a combination of my heart and mind — the lion and the lamb. The lion is the mind and the lamb is the heart. The mind is tricky, the heart is true. That's how I look at it. I trust my feelings. Everything I do comes from my heart. And if it's not, then I'm using my mind to justify or fix it up.

Have you always approached your work in this way or did it take time to get there?

I think it was always that way, but it was still hard to live that way. You know, like being gay for example. Nobody wanted you to be gay. People’s parents thought they were going to run into all these unnecessary hardships. They wanted you to conform and lead the “happy heterosexual life,” you know?

They wanted you to get married. Have kids, be like them. When I was growing up, it just seemed like these people, they didn't seem happy. I wasn't going to do that.

When you compare your early work to your more recent work, what differences stand out to you?

Frankly I don't think much has changed. The major difference is that my work is more of a projection of what I think, as opposed to just capturing something that's in front of me.

I put things together to project an idea about how I feel. That’s different from going to a Black Lives Matter rally and shooting people who are carrying placards. Now I deal with how important it is to contend with ideas, to sit with ideas, to even to have an idea.

You’ve created an extraordinary visual archive of life in the District. What do you hope future generations see or feel when they look at your work?

One thing I hope that they see is that you should follow your heart in terms of what you are drawn to do in life. Do what you want to do. So many people don't 'cause other people have influenced them not to.

Even if you have to do other jobs in order to enable you to acquire whatever it is that you need to be an artist, you have to. Being an artist is a calling, like they say ministers have a calling. Same thing. If you're an artist, it's something that you have to do.

I hope people see that I follow my calling, and that some of the work that I have produced inspires people to look within and to look without.

What continues to excite or challenge you creatively?

What excites me now is adding movement and sound to what I produce, telling stories with added dimensions.

I'm never going to give up being a still photographer. I mean, if I'm 99-and-a-half, I just would be trying to get the camera — or whatever they're going to have — to capture still images … because there is something about that decisive moment when the shutter clicks.

With your help, we pursue stories that hold leaders to account, demystify opaque city and civic processes, and celebrate the idiosyncrasies that make us proud to call D.C. home. Put simply, our mission is to make it easier — and more fun — to live in the District. Our members help keep local news free and independent for all: