Wilson Building Bulletin: A cold dose of reality on D.C.’s budget

And Trayon White gets a new trial date.

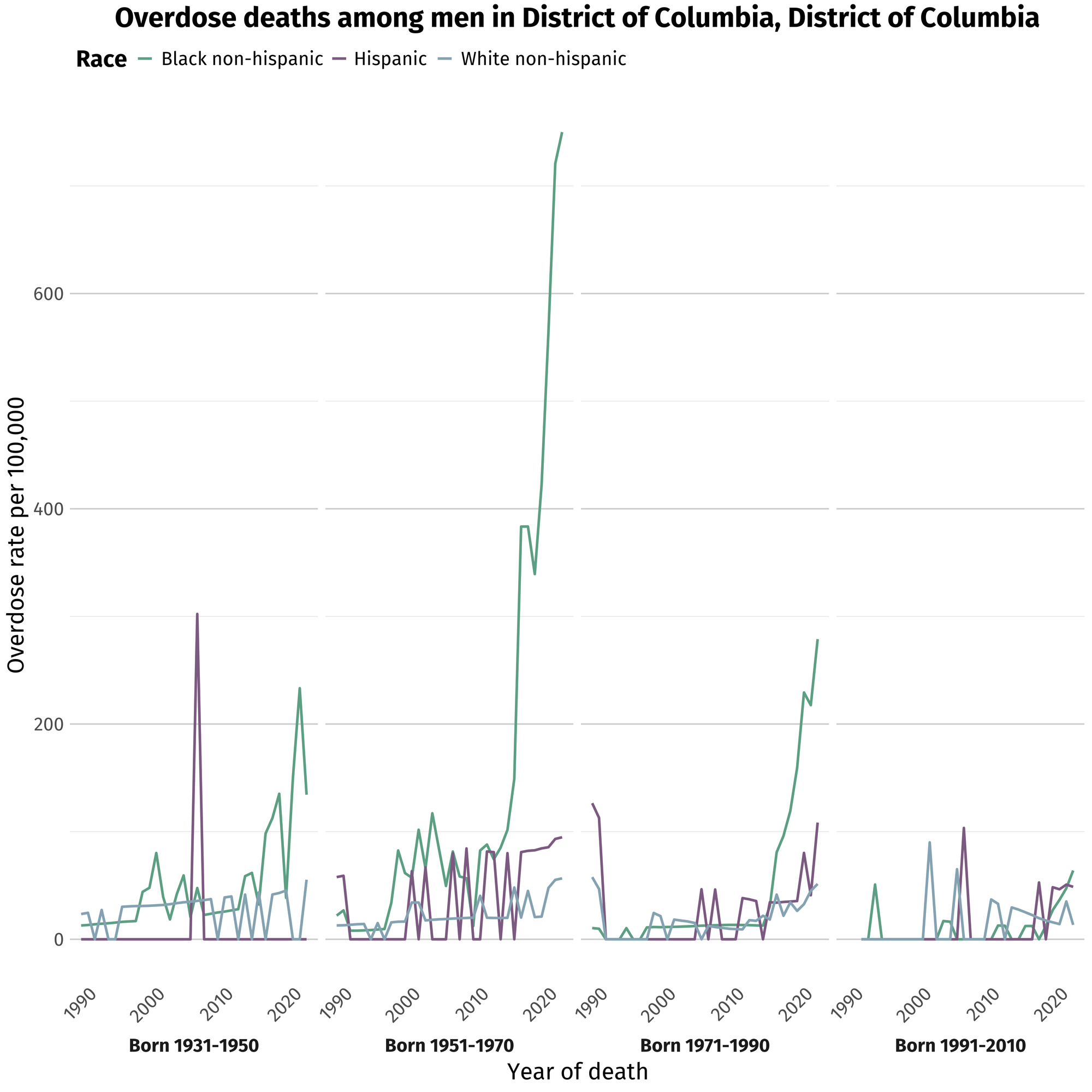

Black men in their mid-fifties to mid-seventies accounted for nearly 38% of the city’s opioid fatalities in 2022, while only making up about 4% of D.C.’s total population.

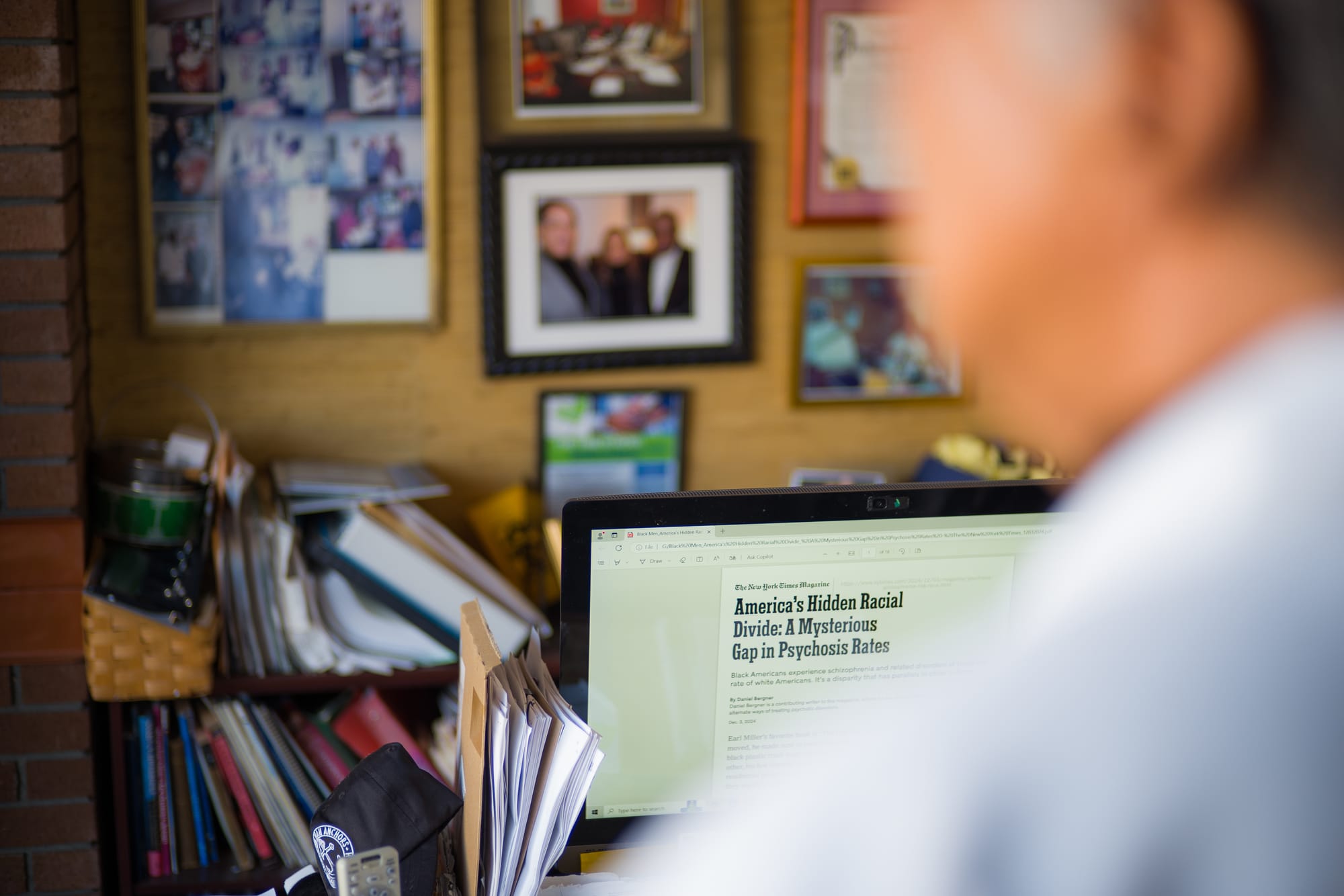

This story is part of a reporting project with The New York Times, The Baltimore Banner, and Stanford University’s Big Local News. These organizations investigated millions of death records to reveal the extent to which drug overdose deaths have affected a generation of Black men in dozens of cities across America. The 51st is one of seven partner newsrooms reporting on the opioid crisis among Black men born between 1951-1970 in cities across the U.S. The data analyzed in this partnership included all U.S. jurisdictions that recorded more than 200 overdoses from 2018-2022. It was reported and photographed with support from Spotlight DC.

Almost three decades had passed since 78-year-old Lance Ward last used heroin, but depression had deepened in his old age. While he’d been out for about seven years, decades of incarceration — and the drug deals and armed robberies that landed him there — cast a heavy shadow. Plus, even after all this time, the cravings still haunted him.

When Ward settled into the passenger seat of an old friend’s car on the D.C.-Maryland border earlier this year, it didn’t seem like a high-stakes decision to use again — he was just looking for a little relief. He’d heard rumors about fentanyl, a synthetic opioid magnitudes stronger than heroin that had overtaken the drug supply in recent years, but he was a veteran drug user. In his heyday, Ward says he routinely used an uncut heroin that he would’ve diluted 15 or 20 times before dealing it.

“I used the pure version of it, so I never thought that some of this stuff that’s out here now could hurt,” says Ward. “Guys who came up like I did in the heroin days — ‘60s, ‘70s, ‘80s — that drug made you feel good, and when you come out of prison, you think it’ll make you feel good again.”

The next thing Ward remembers is waking up in a hospital bed, surrounded by a frenzy of blue-uniformed medical workers scrambling to save his life. He had overdosed on a single hit. If not for his friend slamming on the gas and rushing him to the hospital, it’s unlikely he would have survived.

“All it takes is one mistake, that’s all it takes,” says Ward of using heroin today – which in many cases means using fentanyl, intentionally or not. Fentanyl has become so ubiquitous in drug supplies that in 2023, it contributed to 96% of D.C.’s fatal overdoses.

Ward survived his overdose, but many of his contemporaries haven’t been as lucky. Black men in their mid-fifties to mid-seventies are dying of opioid overdoses at a higher rate than anyone else in the city and — according to a new national analysis — more than anyone else in the country.

Between 2018 and 2022, D.C. saw 2,289 of these men die of overdoses. According to a data analysis by the Baltimore Banner, The New York Times, and Big Local News, Black men born between 1951 and 1970 accounted for nearly 38% of the city’s opioid fatalities in 2022, while only making up about 4% of D.C.’s total population. This disparity is worse than in any other jurisdiction in the data analysis. For context, Baltimore, which has the highest overdose death rate of any major American city in U.S. history, has a smaller overdose death disparity among this cohort.

The problem for these men spans decades. Many of the men overdosing now were longtime heroin users who suffered the worst of D.C.’s heroin epidemic in the ‘60s and ‘70s. While the media coverage around opioids — and accountability for the pharmaceutical companies that kicked off an addiction crisis among largely white prescription pill users — has spurred federal action and attitude shifts, the realities for older Black men continue to go largely unaddressed.

“Black men didn't just start dying,” says Mark Robinson, a 66-year-old who grew up in D.C. and runs a needle exchange and harm reduction services program at Family Medical Counseling Service in Southeast. “We've been dying for decades as a direct result of opioid use disorder. "

Robinson estimates he’s personally lost 50 people to overdoses, including his best friend and college room mate last year.

D.C. recorded a decline in overdose deaths for the first time in six years at the beginning of 2024, though it’s unclear if that trend has sustained through the rest of the year. (The city’s most recent available data only tracks deaths through June 2024.) Still, the emergency among this cohort of Black men appears to be escalating: over the past five years, overdoses among this group have increased at the second-fastest rate in the country, behind only Chicago.

While D.C. has implemented various programs, initiatives, and studies to tackle its opioid emergency in the past 10 years, few solutions have targeted the most vulnerable men. D.C. is receiving millions of dollars from lawsuit settlements with pharmaceutical companies for opioid use prevention, but none of the funds are earmarked for the group that is far and away the most likely to die of an overdose.

Advocates and historians say this repeats a long pattern of neglect for this generation of Black men.

“Even if [the city] were doing a better job focusing on the poor, I doubt that the first people on their list would be a bunch of old guys … who nobody even recognizes exist anymore,” says George Derek Musgroves, who co-wrote Chocolate City: A History of Race and Democracy in the Nation's Capital. “So those guys sort of limp along with a tattered social safety net that they continue to fall through and never really get the type of intervention that will allow them to actually get off of their addiction or to start a new life.”

The situation became more fatal as fentanyl overwhelmed D.C.’s drug supply in the mid and late 2010s — and as the city failed to respond adequately. In 2018, a Washington Post investigation found that D.C. fell woefully behind in distributing overdose reversal drug Narcan compared to other cities with comparable opioid crises, and that the city had failed to execute a federally-funded initiative intended to target long-time heroin users with treatment.

“Our government did not address the problem seriously,” says Dr. Edwin C. Chapman, who has been treating this generation of opioid users for nearly 20 years in his office in Northeast D.C.

While fentanyl is prescribed and administered in doctor’s offices to treat pain, it’s also illegally manufactured in the form of powder, spray, pills, and liquids. It’s 50 times stronger than heroin and can be lethal in doses as small as three milligrams. In 2015, fentanyl accounted for just 20% of fatal drug overdoses in D.C. In five years, it was responsible for 91% of D.C.’s fatal overdoses.

In a statement, D.C.’s Department of Behavioral Health said that it has “put in place over the past five years all the elements of evidence-based practices and best practices that research and experts say will reduce opioid misuse and overdose deaths.” These include, according to DBH, increasing supported housing and employment services for chronic users, providing free rides to treatment, and expanding the availability of Narcan.

“The population of our residents most impacted by illegal drug use historically has been middle-aged African American men so it is no surprise that this population continues to be impacted,” reads the statement. It adds that Black men are also disproportionately represented in treatment and support services.

Advocates say the necessary government solutions for men in this population require going beyond treating the addiction; these men survived not only the onset of the heroin epidemic, but the subsequent crack epidemic, the war on drugs, mass incarceration, and the city’s ongoing and breakneck gentrification. These decades of financial precarity, incarceration, and housing insecurity have impacted not only their physical health, but their mental and emotional well-being.

“Most of our patients… because of the history of racism and oppression, are using drugs. Not because they got it from the doctor's office, but because of trying to relieve mental health stress,” Chapman says, who refers to what this group has experienced as collective post-traumatic stress disorder.

“Many have been sexually abused, many have been in households where there’s drug abuse and alcoholism, unemployment, homelessness,” he says, adding that many of them witnessed shootings and murders from a young age. “They don’t articulate it as such, but that’s what it is — it’s all a part of trauma.”

Ward started using heroin the first time he was incarcerated. He was in his twenties in the late 1960s and a friend at Prince George’s County Detention Center had a way to get drugs inside. When he was first locked up, he says he hardly ever heard about heroin; by the time he got out a few years later, he was using regularly – and it felt like everyone else in his neighborhood was too.

“In a period of a couple years, it blew up,” says Ward. “Everything kind of flipped.”

Those who remember the heroin epidemic of the 1960s say the drug hit certain D.C. neighborhoods, Shaw and U Street among them, like a freight train. The Vietnam War had brought an influx of highly addictive heroin from Southeast Asia – along with many Vietnam War veterans who had gotten hooked while serving – into several American cities. D.C. was among the hardest hit.

“People started experimenting with it and liked the mood-altering feeling that came with them putting the drugs in their system,” says Joe Henery, a 77-year-old Black man who started using heroin in the early 1970s. “That opened a Pandora’s box that is still open to this day.”

Henery grew up in the city when it was a central hub of the Civil Rights Movement. He remembers regularly seeing leaders like Martin Luther King, Jr. and Stokley Carmichael near his house on U Street.

But even in the aftermath of desegregation fights, many Black residents in D.C. faced immense financial disparity and discrimination. The median income for Black people in the city was still 70% of their white counterparts’, and housing discrimination meant Black residents paid 50% more than white residents for similar housing, writes Musgrove and his co-author Chris Myers Asch in Chocolate City. Crime also soared in D.C. around the same time with homicides doubling between 1966 and 1969.

Orphaned at age 10, Henery supported himself as a teenager by robbing banks, executing six stick-ups before he got caught. “The streets gave you a sense of belonging, gave you a sense of family, gave you a sense of somebody caring about you,” he says.

When he finished a seven-and-a-half-year stint in prison for a heist, the friends he robbed with had mostly turned to dealing heroin. When he first joined them, he was committed to not using himself.

“But as time goes on, you can only live in an environment for so long and not do what the environment dictates that everybody else is doing,” he says of the start of a thirty-year-long relationship with the drug.

University of Maryland Professor Brian G. Gilmore grew up near the Fort Totten Metro — and alongside the heroin epidemic of the late 1960s and ‘70s. While he never used it himself, he knew people who were addicted and witnessed the grip it had on certain pockets of the city. He’s had friends pass away from heroin overdoses, and he’s also sat at sober-anniversary events for men in recovery from their addictions.

In 2019, Gilmore published a paper comparing the city’s heroin crisis of the 1960s and 1970s with the government’s response to the current opioid epidemic. According to Gilmore’s research, from 1965-1970, the rate of heroin use in Black residents ages 14-25 tripled, far outpacing the rate for the rest of the city’s population.

This is the same generation of men who make up the majority of D.C.’s overdose deaths today. Some of these young men were returning from Vietnam, according to Gilmore, while others were simply trying to survive a difficult economic landscape.

“If you didn't go to college, you went to the military or you got a job. But D.C. is not a trade town. The trade in D.C. government is bureaucracy … so if you're not working in government bureaucracy or something related to it, the opportunities dry up,” Gilmore says. “Growing up here, you saw that — you saw a large number of Black men lacking in opportunity.”

The city’s government services to address these issues looked nothing like what we have today; during the 1960s and early 1970s, D.C. was still under federal control without an elected mayor or local council. Asch and Musgroves write that with the District’s budget still dictated by Congress, Southern segregationist members retaliated against the advances of the Civil Rights Movement by denying D.C. much of the money and services needed to address the heroin epidemic, poverty, and rising crime, focusing instead on police budgets. The following decades brought much of the same, ramping up mass incarceration in response to the city’s drug problems.

“Nixon, Reagan, Bush, Bush, Clinton, all of them pretty much took the same approach: lock them up,” Gilmore says. “It wasn't any idea of helping people get off heroin; the approach was not treatment, it was not the betterment of the person.”

On a recent Saturday, a group of older Black men met at St. Luke’s Episcopal Church on 15th Street, not far from Logan Circle. It’s fitting that they meet in the church regularly, because many of them say it's only through divine intervention that they’re still alive.

Henery, who hasn’t used in decades, and Ward, who hasn’t used since his overdose 11 months ago, are both part of the group, which calls themselves the Optimistic Gentleman and Ladies, or OG’s, for short. Much of their energy these days is spent doing outreach in schools and on street corners, trying to divert young people from the forces that landed them in prison and on drugs.

“Living in a disenfranchised neighborhood where there’s not a lot of people who are sincerely trying to help you … people who look down on you and they never want to accept you,” says Ward. “I don’t want to see another kid go through what I’ve been through.”

When it comes to drug use, however, it’s their contemporaries who are most vulnerable to an overdose. Barriers like unstable housing, medication dosage limits, and a lack of affordable medical services make just surviving difficult — let alone recovering from a decades-long addiction.

“It’s almost like a death wish [to use at this age], because you’re old now, your body can’t take that punishment like it used to when we were much younger,” says Horace Fletcher, a member of the group who used heroin every day for 30 years. He’s been sober for two decades now but he has close friends who still use regularly.

Two of his friends live at the same retirement home, where he says dealers often hang around when they know social security checks are about to drop. “When they get their check the first day of the month, it's on, it's hoppin’ and poppin’ in those places,” adds Henery in response.

When one of his friends barely survived an overdose last year, Fletcher was dismayed that it didn’t deter him from continuing to use. It wasn’t until the friend developed mobility issues this year that he was forced to quit — it was too difficult to get to his dealer using a walker.

“That’s what stopped him,” Fletcher says. “He couldn’t get to the drugs.”

Fletcher says that D.C.’s worsening housing crisis is another problem many drug users his age face. Starting next year, only 10 to 11 unhoused residents will receive a housing voucher each month — the lowest amount in nearly a decade.

“If you don’t have stability in terms of your living arrangement, and you’re already subject to addictive behavior, that’s a formula for disaster," Fletcher says.

According to data collected by DC Health, unhoused residents made up nearly 30% of all fatal overdoses in 2023. The majority of fatal overdoses occurred in wards 7 and 8. Certain neighborhoods in wards 5 and 6 are also hotspots, like Trinidad and the Southwest Waterfront.

“A major component of healthcare is having a roof over your head,” Chapman says. “I've had patients who have had housing vouchers for 10 years and never got housing and died before they got housing.”

Recently, one of his patients was sleeping on a mattress in the alley behind his office.

Other impediments to treatments are less complex, according to Chapman. In addition to routine medical care, he prescribes his patients buprenorphine, a medication that staves off cravings for opioids. For years, D.C. government and insurance companies have limited how much doctors can prescribe, and how much of the medication can be covered — preventing some longtime heroin users from receiving the doses their bodies need to manage their cravings, according to Chapman.

It took years of lobbying by Chapman and other advocates to get the city to up Medicaid limits this spring, but private insurance companies and Medicare and Medicare Advantage still regularly deny coverage of the doses his patients need to stay alive, he says.

“We lost a lot of patients who were on medication with buprenorphine, but were not comfortable and would drop out, or overdose and die,” Chapman says of patients on lower doses than they needed.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services did not respond directly to these allegations, but say that in 2025 they would begin paying for a new injectable buprenorphine product.

“Providing equitable access to health care services is a key priority for CMS, particularly for those in need of mental health and substance use disorder treatment," reads their statement.

The city’s response to today’s opioid crisis looks, on the surface, drastically different than 50 years ago. While opioid use remains criminalized — and Black residents are more likely to be penalized on drug charges than their white counterparts — the cultural perception of substance use is shifting (both in D.C. and nationwide) away from treating it as a moral failure that should be solved with incarceration, and instead as a medical condition that requires holistic solutions.

And unlike in the '60s and '70s, D.C. now has its own social service departments, a strategic vision for reducing opioid fatalities, and crucially, the money to address the problems. In addition to the local dollars for DBH and DC Health, the city also receives federal money for substance use care.

And after lawsuit settlements with pharmaceutical companies, D.C. has millions of dollars to spend on reducing opioid deaths. Over the next 18 years, the city is expected to receive more than $80 million from the settlements to put toward opioid-use interventions. As of this fall, they’ve used $14 million, according to the commission established to advise fund distribution.

And yet, overdose deaths among these men have ticked up year-over-year — and health advocates have repeatedly criticized city leaders for a lackluster response to a deadly crisis.

“There's no sense of urgency [by D.C. government] whatsoever in targeting Black men that are older,” says Ambrose Lane Jr., a health policy advocate who’s been working in the opioid space for years. He chairs the Opioid Solutions Working Group, an independent coalition of 28 organizations (including some government representatives) that meets monthly to develop and lobby for policy solutions.

But according to the city, Live Long D.C. (the name of D.C.’s strategic plan to reduce opioid fatalities), has “made progress to save and change lives.” Over the past five years, DBH estimates Narcan — which the city provides in schools, churches, and other targeted locations — has reversed 16,000 overdoses. In 2023, peer support specialists in city hospitals linked nearly 1,500 individuals to treatment and 278 individuals were placed in recovery housing, according to a city report tracking Live Long D.C.’s achievements.

But both Lane and Chapman say they have pushed the city to implement several evidence-backed solutions, sometimes to no avail.

Chapman was appointed to the D.C. committee established to advise the city on how to spend its opioid settlement dollars, but resigned in frustration at how the funds were being handled, he says. He lobbied unsuccessfully for some of that money to go toward contingency management — a treatment program that gives financial incentives to patients in exchange for staying sober. He also wants the city to create a registry for people brought into hospitals when they overdose, so government workers and medical providers can be better equipped to help in the aftermath. Currently, he says it’s a “revolving door,” where patients are often discharged from the emergency department and jail without necessary follow-up care or resources.

And while the increase in dosage caps for buprenorphine is helpful, Chapman maintains that the city is overlooking clear opportunities to save lives — namely by putting vulnerable patients in stable housing. He often takes it upon himself to pound the pavement, sometimes with members of the OGs, looking for available units his patients might be able to move into. He points to the tens of thousands of vacant properties in the city as proof that there’s just not enough political will to solve a central problem that keeps his patients unhoused and addicted.

“They found $500 million to give to the owner of the Capitals and the Wizards to renovate the basketball arena but they can't find money to house these folks," Chapman says.

Lane, who for years pushed the city to declare a public health emergency over opioids (which it finally did in 2023), says D.C. is missing more brick-and-mortar treatment and housing locations for men in impacted wards, and that many of the piece-meal solutions from the city don’t address the full scope of these mens’ realities, which often include financial insecurity, unemployment, housing insecurity, and other mental and physical health issues. He’s lobbying for the creation of a new office in the health department dedicated to health solutions for Black men.

“Graduation rates among Black boys, homelessness among Black men, unemployment among Black men, all of those things are intertwined,” he says.

City officials, though, are looking hopefully toward the coming year, after 2024 saw the first decline in overdoses in years. “We are keeping our foot on the gas—doubling down on what’s working and developing new strategies to address new challenges,” reads a DBH statement. As of June 2024, D.C. had recorded 196 fatal overdoses, a 24% decrease from that same point in 2023. Experts are still analyzing the cause of the downward shift.

And while some see it as a promising turn, it could be a sign that many of these men— who accounted for most of D.C.’s deaths over the years — are dying out.

Henery says he only has two male friends he grew up with who are still alive today. Ward says that these days, he hears regularly about acquaintances who died from fentanyl overdoses — friends of friends around his age that he knew in the drug world, or people who were incarcerated at the same time as him.

“There were people that had awesome potential and the drugs just took it away,” he says.

This story was edited by Christina Sturdivant Sani and Natalie Delgadillo.

With your help, we pursue stories that hold leaders to account, demystify opaque city and civic processes, and celebrate the idiosyncrasies that make us proud to call D.C. home. Put simply, our mission is to make it easier — and more fun — to live in the District. Our members help keep local news free and independent for all: