What can be done about your expensive Pepco bill?

Financial assistance, energy audits, and avoiding third-party suppliers can help.

Here’s everything you need to know about Initiative 83, appearing on your ballots this fall.

The way most of us have come to think of it, voting is a pretty simple concept: you get your ballot, you choose the best candidate for a particular office, your vote gets counted, and a winner is declared. But a measure appearing on this year’s ballot in D.C. could dramatically upend that process, and open critical elections to tens of thousands of new voters.

We’re talking about Initiative 83, a ballot measure that seeks to bring ranked-choice voting to the city’s elections and to allow independent voters – those not registered as a Democrat, Republican, or Statehood Green – to participate in the city’s primary elections, which are currently only open to voters registered with those parties. (A ballot initiative is an opportunity for residents themselves, rather than a legislative body, to propose and vote for a measure that changes current law. In D.C., at least 5% of registered voters have to sign a petition for an initiative to get on the ballot.)

Read below for everything you need to know about Initiative 83. And DON’T FORGET! When you vote, flip your ballot over to cast your vote for or against it.

Most elections in the U.S. – including in D.C. – operate according to the basic principles that each voter gets to pick a candidate in a specific race and that the candidate with the most votes wins, whether they get a majority of votes (more than 50%) or a plurality (less than 50%, but more than their competitors). This is called plurality or first-past-the-post voting.

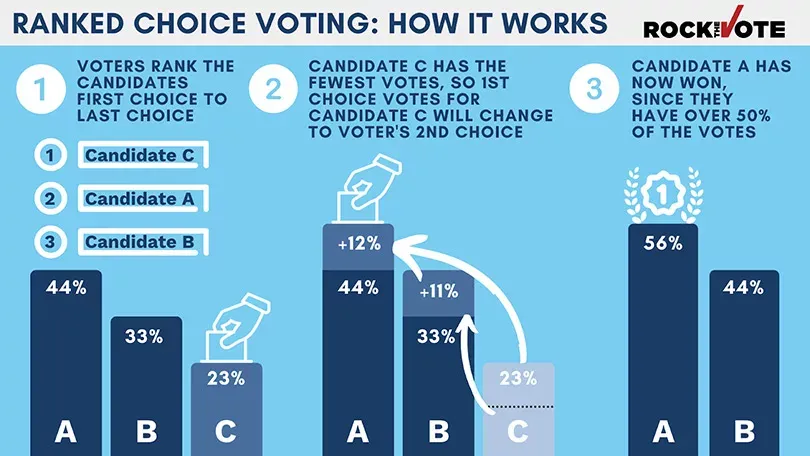

Ranked-choice voting, on the other hand, allows voters to rank candidates in order of preference.

Say there are five candidates for a particular office; you’d get to rank them 1 through 5 on your ballot, one being your favorite. When the votes are tallied, all the first-ranked choices made by voters in a particular race are counted. If one candidate gets more than 50% of first-choice votes in that first round, they win the election. But if no one reaches that threshold, the lowest-ranked candidate gets dropped and the remaining votes are reapportioned to the candidates that haven’t been knocked off the ballot. (So if you gave your highest ranking to a candidate that gets dropped after the first round, the candidate you picked second will then get your vote.) This cycle can continue until one candidate crosses the 50% threshold and wins.

Still a bit confused? Rock the Vote has a chart explaining the process; this video also unpacks the system, albeit with ice cream flavors instead of candidates.

Other jurisdictions that use ranked-choice voting include Takoma Park, Maryland; Arlington, Virginia; New York City and more.

Proponents of Initiative 83 say their goal is to ensure that candidates elected to office have the support of a majority of their constituents.

One of the biggest drawbacks of the city’s current system, they say, is that the winner of a crowded contest may only get a relatively small fraction of the total votes cast. In a fictional scenario where you have five candidates running for mayor, the ultimate winner could come away with, say, 33% of the vote – well below majority support.

Additionally, supporters of ranked-choice voting say the system gives voters the opportunity to vote for candidates they truly believe in without worrying about the spoiler effect or about throwing away their vote on a candidate who seems unlikely to win.

To use the ice cream metaphor: you may truly love mint chocolate chip, but you also know that cookies and cream and rocky road are generally better liked by most people. You prefer cookies and cream to rocky road, and don't want to help rocky road win by casting your vote for your true favorite (mint and chip). That means under the current system, you may end up voting for cookies and cream even if it's not your true first choice.

With ranked-choice voting, however, you could give your first choice to mint chocolate chip while ranking cookies and cream second, aligning your vote with your true preferences without concern that your vote will either be a throwaway or circuitously aid your least favorite choice to win. (We all know that coffee ice cream is the only real choice, but we’re strictly objective here and won’t force our obviously correct opinions on anyone else. Go ahead and enjoy mint chocolate chip, if having no taste whatsoever is your only goal in life.)

Proponents also believe that ranked-choice voting would minimize negative campaigning, largely because candidates would be deterred from attacking any candidate in the hope that that candidate's supporters might still rank them second on the ballot.

Proponents say Initiative 83 will increase participation in the city’s elections by expanding the universe of voters who can participate in primaries, where turnout in 2022 was a paltry 32%.

You might know someone in D.C. who is registered as an independent either because they have the type of job where they shouldn’t openly side with either of the two major political parties, or maybe because they just don’t fully agree with either one when it comes to local issues. And that person isn’t alone: there are more than 75,000 independent voters in D.C., representing roughly 17% of the entire electorate.

Independent voters don’t get to cast ballots in primary elections, and in a place like D.C. – where the winners of the Democratic primary largely cruise to victory in the general – that can mean foregoing a significant opportunity to have their voices heard. Proponents have gone so far as to calling the current system “voter suppression,” and argue Initiative 83 would change that by allowing independent voters to vote in primary elections.

Now, to be clear: Initiative 83 wouldn’t create completely “open” primaries in D.C., where a voter could simply show up to vote and decide on the spot which primary they want to vote in. (Virginia, for example, has an open primary system, though voters there don’t register with a political party.) Rather, the initiative would create a semi-open primary, because independent voters would have to notify the D.C. Board of Elections ahead of any primary to declare which primary they’d want to vote in (Democrat, Republican, or Statehood Green). Their voter registration, though, would remain unchanged. Any broader change to how primaries are run – say, to eliminate partisan primaries or instead move toward a “jungle” primary – would require amending the city’s Home Rule Act, a more complicated process.

That would be the Make All Votes Count D.C. campaign, which is led by Ward 7 ANC Commissioner Lisa Rice and longtime Ward 8 political activist Phil Pannell. The lion’s share of the campaign’s funding (almost $500,000 as of the end of September) has come from boutique soapmaker Dr. Bronner (yes, really; the company bankrolls plenty of progressive causes across the country, and last kicked in for a D.C. ballot initiative on magic mushrooms); Silver Spring-based election reform group FairVote; and even D.C. philanthropist and power player Katherine Bradley.

The Washington Post’s editorial board, The Sunrise Movement, two councilmembers, and a handful of ANCs have come out in support of the initiative. (For a full list of endorsees, click here.)

While some critics of the initiative oppose both ranked-choice voting and allowing independents to vote in primaries, others more passionately object to one or the other. But the initiative doesn’t allow for voters to choose between ranked-choice voting or more open primaries; it’s a package deal with a single yes or no vote. (Organizers of the Initiative 83 campaign say that this is because the proposals are complementary, but also because separating them would have forced them to run two campaigns, collect signatures on two different petitions, and so on.)

Critics of ranked-choice voting say that the system would ultimately be too complicated, possibly resulting in confused voters disenfranchising themselves by not ranking their preferences for all the candidates in a particular race. And they worry that the impact of that potential confusion could be more severely felt in low-income communities in D.C. An analysis of the first election in New York City that used ranked-choice voting somewhat showed this pattern; voters in wealthier parts of the city were more likely to rank all of their preferences, while voters in less affluent areas were not. Other research, however, has shown that once voters use ranked-choice voting once, they get used to how it works.

Concerns over the additional complexity of ranked-choice voting have even spurred a ballot measure in Alaska that, if passed, would repeal the state’s four-year-old experiment with the system of voting. And states like Florida, Kentucky and Tennessee – spurred by conservative activists – have even gone as far as to fully prohibit localities from even considering implementing ranked-choice voting.

As for opening primaries to independent voters, critics say that Initiative 83 would unfairly allow unaffiliated voters to influence the direction of a political party they are not even ideologically committed to. So, since D.C. is largely a Democratic town, some are concerned that conservative-leaning independent voters with no allegiance to the Democratic Party and its principles could play an outsize role in determining who wins and loses specific races. If someone wants to vote in a primary election, the argument goes, they should just register with one of the political parties that has primaries. (In D.C., you can change your party affiliation on your voter registration up to three weeks before a primary.)

In large part, the D.C. Democratic Party – though, even there, different factions have emerged. Many of the city’s Democratic leaders and elected officials – including Mayor Muriel Bowser and D.C. Council Chairman Phil Mendelson – oppose Initiative 83, either as a whole or specific components as we laid out above. The D.C. Democratic Party sued to try to keep the initiative off the ballot, and recently sent out a citywide mailer urging voters to reject it. That prompted a quasi-controversy of its own, when some members of the Democratic Party’s leadership who were named on the mailer said they actually support Initiative 83 or haven’t yet decided which way they’ll vote and were never told that the mailer would be sent out to voters. Never a dull moment.

Not exactly.

While Initiative 83 wants ranked-choice voting and semi-open primaries in place by 2026, the initiative was written to be subject to appropriations; in short, if voters approve it, the D.C. Council would still have to pay to implement it. It’s not much money – roughly $2.7 million over four years – but it remains unclear whether councilmembers would want to spend the money making I-83 a reality.

Support for ranked-choice voting on the council has always been soft; that’s why past legislation to bring it to the city’s elections never got much further than public hearings. And more recently, both the City Paper and Washington Post have reported that few councilmembers are jumping to express their support for Initiative 83, in part because they may support ranked-choice voting or semi-open primaries – but not both.

The dynamics of a possible victory for Initiative 83 could further determine the politics around whether the council decides to fund Initiative 83 or not. Should the city’s majority Black areas – wards 5, 7, and 8 – vote against it, councilmembers may feel even more hesitant to fund the initiative.

We’re shocked you don’t know that the cherry is D.C.’s state fruit. (File that away for the next trivia night.) Additionally, when picked, cherries come in pairs – and the initiative has two parts to it.

With your help, we pursue stories that hold leaders to account, demystify opaque city and civic processes, and celebrate the idiosyncrasies that make us proud to call D.C. home. Put simply, our mission is to make it easier — and more fun — to live in the District. Our members help keep local news free and independent for all: