Wilson Building Bulletin: To fight (Congress) or not to fight, that is the question

D.C.'s elected officials need to decide whether to defy Congress – or defer to it – over a tax bill.

Plus: Solving the mystery of a new helicopter, and trying to get Congress to cough up more money for police.

It’s been just over a week since President Trump’s 30-day crime emergency in D.C. officially ended. While over 2,000 National Guard troops remain deployed throughout the city, the end of the emergency meant that Trump ceded control over the Metropolitan Police Department back to local officials.

For now, at least. Earlier this week Trump took to Truth Social to threaten to declare another emergency and re-federalize the police, complaining that Mayor Muriel Bowser had decided that MPD should stop working so closely with ICE.

“If I allowed this to happen, CRIME would come roaring back,” he wrote. “To the people and businesses of Washington, D.C., DON’T WORRY, I AM WITH YOU, AND WON’T ALLOW THIS TO HAPPEN. I’ll call a National Emergency, and Federalize, if necessary!!!” (This would require another executive order declaring an emergency and citing the provision of the Home Rule Charter that allows him to temporarily take control of MPD.)

Trump’s declaration is a harsh reminder for D.C. that while one so-called emergency ended, there isn’t much stopping him from just declaring another at any point over the next three years of his term.

Even if he doesn’t, it still remains unclear how long federal law enforcement officers will remain active in D.C. Bowser has largely said they are welcome to stay, though she has gently asked that they follow the city’s lead and collaborate where local police think they would be most useful.

That welcome, though, hasn’t exactly been extended to ICE. Bowser only lightly criticized its presence during the emergency, but she has more directly indicated that she would rather not see them around now. “Immigration enforcement is not what the MPD does. And with the end of the emergency, it won’t be what MPD does in the future,” she said last week.

But even without another declared emergency, ICE can freely remain active in the city. And how much MPD works with them – if at all – is an open question.

During the 30-day emergency, D.C. police officers set up traffic checkpoints where ICE was seen checking IDs, for example. An order issued by D.C. Police Chief Pamela Smith allowing limited cooperation with ICE remains on the books, but city officials have largely avoided answering questions about whether any meaningful cooperation is still happening.

During a day-long hearing before the House Oversight Committee on Thursday, Bowser generally stayed away from talking about what ICE had done in D.C. – or might continue to do. D.C. Council Chairman Phil Mendelson, though, spoke more forcefully about the agency’s aggressive presence.

“To the extent the recent federal activities here have had any positive impact at all, that impact is blunted by the fact that residents equate it with whatever ICE has decided they need to do in our neighborhoods,” he said. “If ICE must continue its operations in the District, they need to change their tactics, stop hiding behind masks, discontinue racial profiling, cease detaining lawful immigrants, and afford detainees due process.”

That’s a big ask, though – and not one that Trump is likely going to agree to.

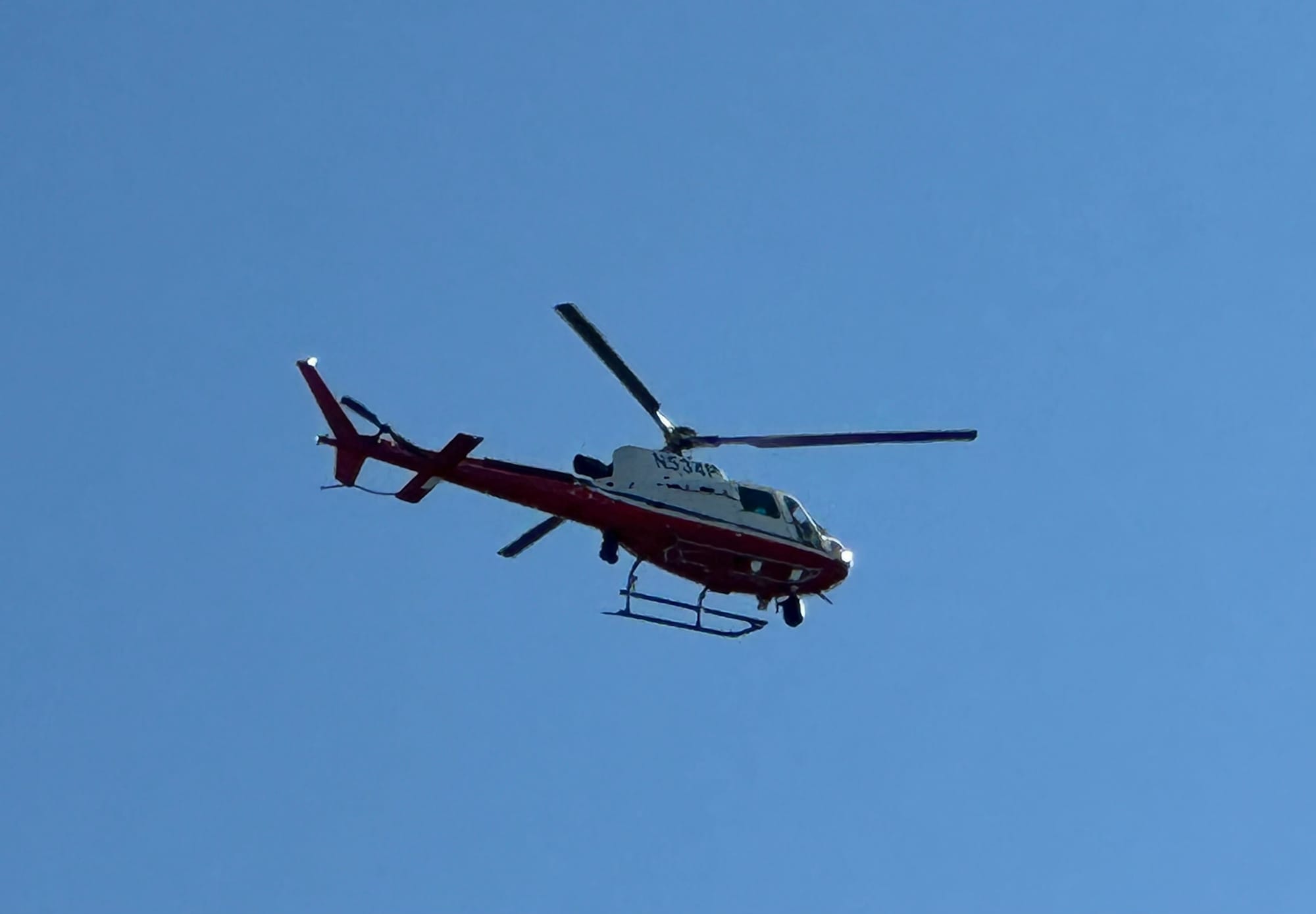

A consistent complaint about ICE agents in D.C. has been that they’re usually masked. But a secondary concern about the agency’s activities has also been buzzing around: a white and orange helicopter.

Residents in particular neighborhoods – often on the east side of D.C. – have complained over the last month of a helicopter circling overhead, often for hours at a time and for an unclear purpose.

“It has been a nuisance for several days and is affecting my sleep, the sleep of a little one, and is very disconcerting,” wrote one resident in a Facebook group for residents of Brookland and Woodridge. Another echoed: “Last night, as we’re trying to put our small children to sleep it was so low it was rattling our windows. One child could not stay [asleep] and kept getting up.”

I recently spotted it doing a circuit over Hill East, Kingman Park, and neighborhoods east of the Anacostia River for more than an hour.

Unmasking the helicopter became a quest of sorts for Zahid Rathore, an ANC commissioner who represents parts of Woodridge. Using public flight trackers, Rathore learned that the helicopter wasn’t using ADS-B, which produces signals that would allow the public to track its registration, origin, and flight path. (MPD’s helicopter uses ADS-B, making it easily trackable when it’s in use.)

Rathore put the question to MPD officials, and he did ultimately get a response: The helicopter belongs to Customs and Border Protection, and it has been deployed as part of President Trump’s federal surge in D.C.

“This is CBP doing surveillance on our people,” Rathore told me. “We live in an area where there is heightened security, but since this occupation, this CBP helicopter is an addition. How much helicopter surveillance do we need?”

The Department of Homeland Security confirmed to The 51st that the helicopter does indeed belong to CBP, and that it can “provide a unique one-of-a-kind mission set that provides enhanced officer safety while also providing critical situational awareness for law enforcement operations.” The department said it wasn’t being used to monitor protests.

Still, Rathore and others are concerned that the helicopter isn’t using ADS-B. Members of Helicopters of D.C. – a loosely organized collective of chopper-spotters – tell us that they have been raising the issue with federal officials for years; There’s a relatively broad exemption for national security purposes. But their worries about it potentially being abused came into sharper relief when a military helicopter, which wasn’t using ADS-B, collided with a passenger jet coming into National Airport, killing 67 people earlier this year.

“Besides the fact that helicopters crashed into a plane not using ADS-B, which is a safety feature, there’s also the surveillance concern because we know they have advanced sensors on them,” said a member of the group, who asked not to be identified by name because the issue touches on sensitive federal security agencies.

And for Rathore’s neighbors, there’s also a practical issue: If you can’t identify a helicopter, it’s much more difficult to find out who you can complain to about it.

“I asked MPD what was going on, because if it was MPD we would have at least some recourse,” Rathore says. “Now that it’s federal they’re going to ignore everything.”

There’s not much D.C. residents can do to stop federal agencies like CBP from hovering overhead, but there is a push to require them to be more easily identifiable. Legislation currently in the Senate – sponsored by Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Texas) – would impose stricter requirements for the use of ADS-B for helicopters flying in and around the city.

In mid-August, a resident spotted a pair of D.C. government dump trucks blocking access to a street just north of the White House. They weren’t doing trash duty, though, but rather providing additional security for a delegation of European leaders meeting with President Trump.

Those dump trucks are just one of the unseen and underappreciated services that D.C. provides the federal government – and for which city officials say federal reimbursements have often fallen short. Those shortfalls have happened for years, and exemplify the ways in which the federal government doesn’t always shoulder its share of the burden of making D.C. safer – even as Trump and other Republicans lambast the city for how it handles crime and other issues.

All of this starts, as so many things in Washington do, with an acronym: EPSF. Formally known as the Emergency Planning and Security Fund, it’s a pot of money funded by Congress that is meant to reimburse D.C. for any expenses related to the federal presence in the city. That usually means paying for police overtime, but it can also be other expenses like the use of those dump trucks.

“It recognizes the District provides a number of services to the federal government,” says one senior D.C. official, who asked not to be identified by name in order to speak more frankly about the fund. "This is a place where people come to protest and air their grievances, and this fund has always envisioned that the District is best positioned to provide that support on city streets. There is an inordinate burden … that other jurisdictions don’t have because they are not the federal district.”

Of course, nothing in the world is free, and these services cost money. And that’s where EPSF comes in: D.C. can request reimbursements whenever local police work overtime on a big protest downtown or block roads for a presidential motorcade, for example.

But those costs have grown in recent years, even as the amount Congress has put into the fund hasn’t increased much. In 2022, for example, Congress put $25 million into EPSF – but D.C. incurred $46.2 million in expenses. The difference came out of local coffers. In 2023, the gap between what Congress allocated (then $30 million) and what D.C. ended up spending was smaller – only $5.9 million. But it jumped back up again last year, to $26.5 million.

All told, D.C. has spent almost $84 million of its own money to cover federal security needs over the last five years.

“We’re not complaining about the additional work because we think we do it best, but there is a cost,” Bowser told me recently. “In recent years the payment hasn’t matched what it costs.”

Congress increased the fund this year to about $90 million. But that’s because there was a presidential inauguration, which dramatically increased local expenses. City officials say that even that money won’t go far enough – by July they were estimating the city would be on the hook for $9 million in local funds, and that was before Trump’s federal surge and any additional local costs that would bring.

“We’re nervous about any prolonged federal surge or if Trump decides to do another emergency and … what spending pressures that would put on our security apparatus,” says the city official we spoke with.

D.C. is now pushing for a significant increase in the annual congressional appropriation to EPSF, from the usual $30 million to upwards of $90 million a year. City officials say that while congressional Republicans didn’t used to be particularly receptive to requests for more money for EPSF, Trump’s focus on public safety has changed that. A draft spending bill in the House, for one, would put $70 million into EPSF for the coming year. (A Democratic alternative would have given $100 million.)

D.C. Council Chairman Phil Mendelson told House Republicans at a congressional hearing on Thursday that every dollar the city spends paying for something the federal government doesn’t is a dollar not spent fighting crime in the city.

“I stress: these payments to MPD are not a grant, they are reimbursement,” he said. “Full reimbursement is an easy way for Congress to help improve public safety in the District.”

With your help, we pursue stories that hold leaders to account, demystify opaque city and civic processes, and celebrate the idiosyncrasies that make us proud to call D.C. home. Put simply, our mission is to make it easier — and more fun — to live in the District. Our members help keep local news free and independent for all: