Baby steps: Janeese Lewis George pledges universal affordable child care for D.C.

It’s not free, and her plan faces fiscal challenges.

"We're just trying to live."

In a move that sent shockwaves through city residents, particularly those experiencing homelessness and service providers, President Donald Trump federalized D.C.’s Metropolitan Police Department (MPD) and deployed the National Guard to D.C. on Aug. 11.

In his announcement, Trump, who has frequently linked crime and homelessness, framed unsheltered homelessness and encampments as part of the city’s alleged crime problem. He directed law enforcement to remove tents and threatened to remove people experiencing homelessness from the city.

Over the following days, homelessness outreach workers scrambled to help people find safe places to sleep, putting them up in hotels or moving them into shelters, while fear, uncertainty, and frustration grew.

“You’re breaking people’s lives, and dreams, and their livelihoods. You’re messing people’s livelihoods up,” Temitope Ibijemilusi, who often sleeps downtown, said after law enforcement made him move his belongings. “You’re causing more problems, causing more anxiety.”

In total, Street Sense has confirmed that at least 20 people have been displaced from eight encampments through federally driven closures. Law enforcement told many more people to move from public spaces where people experiencing homelessness often congregate. Closures have largely been led by law enforcement officers, rather than the city’s normal outreach teams.

Though White House Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt said 48 encampments have been closed since Aug. 11, Street Sense has not been able to confirm closures at more than eight unique sites across the District. The White House did not provide a list of closed sites or sites it intends to close.

Data from the city, meanwhile, suggests the number of people living in encampments did not meaningfully decrease over the last two weeks.

Meanwhile, dozens of people living outside reported harassment, fear, or uncertainty stemming from federal actions and rhetoric. Though the Trump administration threatened the criminalization of camping, panhandling, or sleeping outside, publicly available local arrest data and data provided by the White House do not yet show any arrests with those charges.

In response to the crackdown, the city opened more than 100 additional shelter beds, according to the D.C. Department of Human Services (DHS), and is prepared to open more if needed. A second noncongregate shelter will open in the next few months, providing additional beds, and the city will put more money towards its homelessness diversion program.

But not everyone feels safe going into shelters — Kevin, who sleeps outside the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Library downtown, said he finds the facilities overcrowded, and he worries about getting sick. So instead, he sleeps outside. These days, he feels particularly vulnerable to law enforcement.

“We already know what’s going on,” Kevin told Street Sense on Aug. 19, sitting outside MLK as the sun set. “I don’t know when, sooner or later, but they gonna come. They gonna come.”

On the night of Aug. 14, faced with FBI agents and a swarm of press, Meghann Abraham decided she was going to stand in front of her tent, cross her arms, and face the onslaught. She knew she wasn’t doing anything wrong — no matter what the president of the United States might say.

“Being homeless is not a crime,” she told Street Sense a few hours before. “We’re not drug addicts. We’re not criminals. We don’t have guns or nothing. We’re just trying to live.”

Abraham, who’s 34 years old, recently earned an associate’s degree from the College of Southern Maryland in the applied science of Homeland Security. She’d like to work for FEMA someday, helping people in crisis. After moving from the MLK Library, she lived with her boyfriend in a tent on the edge of Washington Circle for the past couple of months.

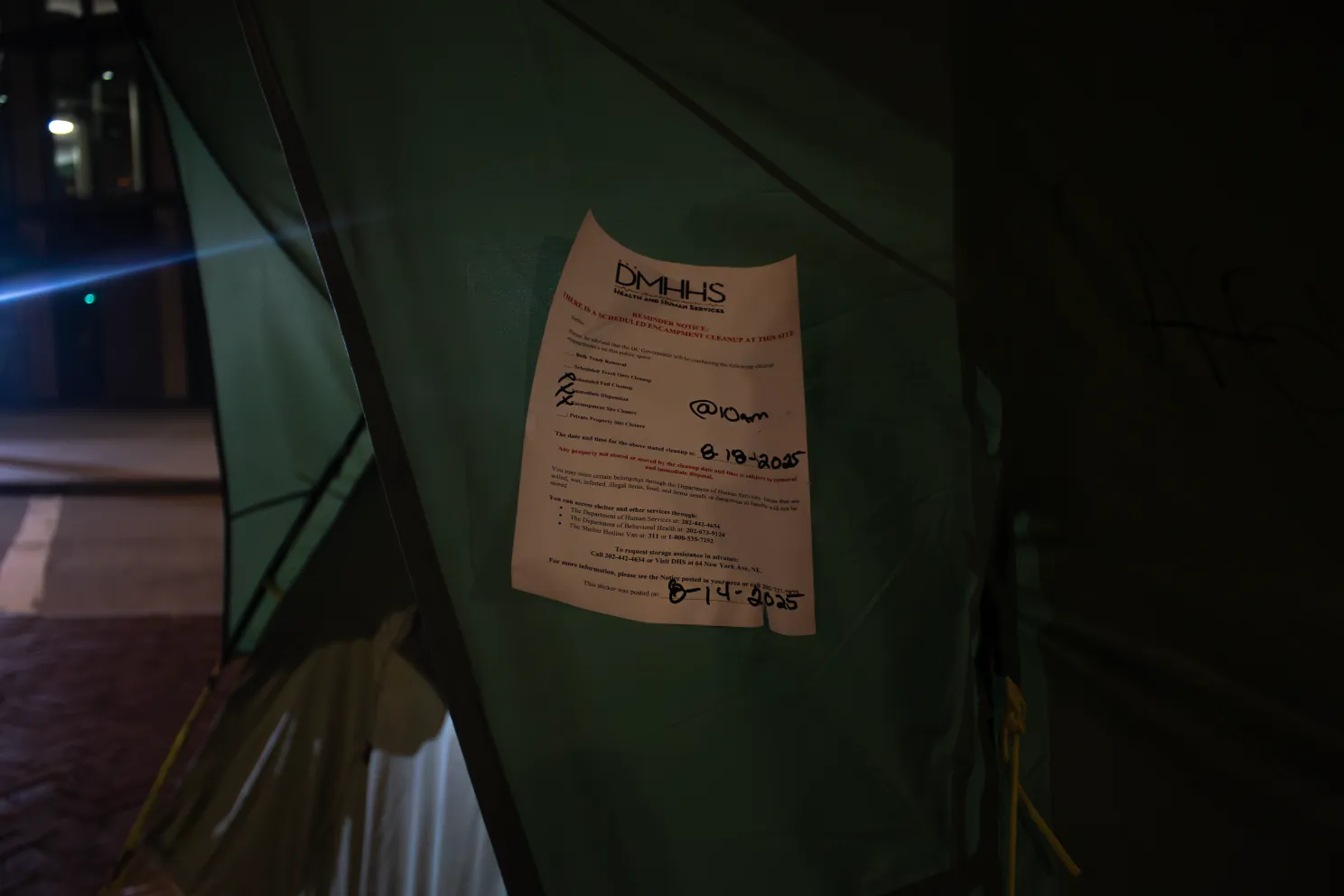

On Aug. 14, whispers began federal agents would start closing D.C.’s encampments. Late that afternoon, the city placed stickers on several tents in Washington Circle, notifying residents the encampment would be closed four days later, on Aug. 18. At the time, outreach workers and local officials said they did not know what locations federal agents would be targeting. They learned the plans only shortly before the FBI arrived.

Just after 9 p.m., at least 12 FBI agents arrived at Washington Circle, intending to remove several tents, including Abraham’s.

When agents approached Abraham, she showed them the sticker from the city. With the support of legal advocates, she argued she had the right to stay until Aug. 18. Agents eventually left, and though they returned once more, they were seemingly deterred by the sticker. That night, they closed neither Abraham’s encampment nor the four nearby ones they told city officials they’d be visiting.

But the FBI agents’ departure that night was a brief reprieve. Local law enforcement returned to Abraham’s encampment, as well as several others, on the next morning, closing them on the orders of the federal government.

Officers were first spotted near the city’s Downtown Day Services Center, where many people experiencing homelessness go to get meals, showers, IDs, and other assistance. Residents and outreach workers said officers threw away some of the belongings of people in the area. Staff for nearby programs tried to keep people inside to make sure they stayed safe, accompanying clients outside to keep watch on them during their smoke breaks.

Ibijemilusi just recently began living outside the center, after the person he had been staying with passed away. He told Street Sense that law enforcement told him to break down his tent and discarded some other people’s possessions.

“A lot of people lost their things today,” Ibijemilusi said.

MPD then went to the tents near Washington Circle and told Abraham she had to move or risk arrest. Her boyfriend was at work at the time. MPD also threw away the tents and belongings of other encampment residents, even as Abraham scrambled to get in touch with them.

“They were [asking] is this trash? Is this trash? And I was, like, none of my stuff is trash. I have all these things because I want to own them,” Abraham told Street Sense reporters who arrived as the forced displacement was underway. “But then it’s me trying to advocate for myself against 20 police officers.”

MPD then headed down the street to 26th and L, where officers removed three tents, displacing at least one resident. Next, MPD officers headed downtown to a structure near 15th and G Streets and removed the structure. It did not appear that a resident was present.

In total, officers cleared at least 11 tents on Aug. 15 — most thrown into a Department of Public Works truck that accompanied law enforcement. The effort was led and conducted by MPD, rather than federal law enforcement. The Office of the Deputy Mayor for Health and Human Services (DMHHS), which normally runs encampment closures and clearings in the city, was not involved in the closures, according to a statement from the agency. Street Sense also did not observe the usual presence of city social support agencies at any of these closures, other than two DHS officials at 15th and G Street.

“The District had a scheduled engagement to close the site at Washington Circle on August 18,” a DMHHS spokesperson wrote that afternoon. “However, today, federal officials chose to execute the closure at the site and several others.”

Jim Malec, an ANC commissioner for the area, said he was angry MPD closed the encampment early, and concerned about the city government’s possible compliance with Trump’s directives.

“To promise these people a Monday deadline and then destroy their property three days early is simply cruel, and we must ensure that whomever is responsible for this decision is held accountable,” Malec wrote in a statement to Street Sense.

When Street Sense called Abraham a few days later and asked her about the closure, she described the experience as “violating.”

The most recent federally driven encampment closure Street Sense identified was on Aug. 18, when MPD officers again visited the area by the city’s Downtown Day Service Center. Officers stood outside the center for about an hour as outreach workers and day center staff helped people leave the area. Despite fears that U.S. Marshals would be on the scene, the engagement was conducted by local police and DMHHS.

A DMHHS official on site told Street Sense the clearing was a “White House-mandated engagement.”

One man, who gave his name as Willie Nelson, said he was waiting outside the center in hopes of getting an ID. The center distributes IDs only on Thursdays, and has a limited number each week, so Nelson said he was sleeping nearby until then, hoping to beat the rush.

“I’ll be the first in line,” he said.

D.C. is made up of a mix of local and federal land. Under normal circumstances, those boundaries dictate if encampments are closed and which authorities lead the closure.

Encampments on federal land, such as the C&O Canal, Rock Creek Park, and green space near monuments and federal buildings, are cleared at the discretion of the National Park Service (NPS). NPS and its associated law enforcement, Park Police, began reinforcing camping bans in May 2024. They accelerated in March, after Trump issued an executive order to “make the District of Columbia safe and beautiful.”

Between March and early August, the agency cleared 70 encampments, Secretary of the Interior Doug Burgum said at an Aug. 11 press conference. At the start of the federalization, two encampments remained on federal land, Leavitt said at an Aug. 12 press conference.

The city has its own process to respond to encampments on local land, using a team from DMHHS to track, conduct outreach with, and sometimes close encampments. The city has closed at least 60 encampments since the beginning of the year, according to data compiled by Street Sense. According to DMHHS, as of the start of Trump’s takeover, there were 62 encampments in the city. About 100 people lived in them, though far more people sleep outside on any given night; at least 800, according to the most recent count.

Trump’s federalization upended the normal encampment process. His oversight of the local police (which, even when limited, means the federal government has discretion over how police interact with encampments) turned MPD officers into encampment teams as part of his bid to remove the “drugged-out maniacs and homeless people” he says have taken over the city.

“This is his issue, seeing homeless encampments — it just triggers something in him,” Mayor Muriel Bowser said in a live community chat streamed on X Aug. 12.

The city was the first to begin unscheduled and expedited encampment closures, visiting spots near the Kennedy Center on Aug. 13 to inform residents they should move their tents over the next day. (Trump was at the Kennedy Center the same day.)

On Aug. 14, the city closed the encampment that had initially drawn Trump’s ire in a Truth Social post, in which he accompanied photos of tents along the interstate with the sentiment “The Homeless have to move out, IMMEDIATELY.” Under D.C. protocol, the closure was an immediate disposition, an encampment closure in which residents only have 24 hours’ notice as opposed to the standard 7 days’, making this closure comparably hurried.

Rachel Pierre, the interim head of DHS, said the closure was a response to the August executive order and that other sites could be closed in the coming days. Deputy Mayor for Health and Human Services Wayne Turnage and other city officials suggested the city was more qualified to close encampments. While trying to stay ahead of federal closures, officials emphasized they had more services to offer residents.

“Closing encampments is a very, very complex process, you are dealing with human beings who, in many cases, have been marginalized, their lives are being disrupted,” Turnage told reporters on Aug. 14. “We felt that if the site was going to be closed, because it was a sizable site, we should do it ourselves,” he said, referring to the seven tent encampment along the interstate.

City outreach workers had been in the area since Trump’s Truth Social post, working with encampment residents, who were on high alert if they had not already moved. One man, G, told Street Sense on Aug. 11 that he was planning to move that day because of the attention the encampment began receiving.

Another, George Morgan, said he was hopeful Trump and Bowser could come to an agreement. He said he was interested in moving into one of the shelter spots the city had recently opened. But to do so, he would have to leave behind Blue, his beloved dog; the city’s shelters don’t accept pets.

Despite Morgan’s hopes, the Aug. 14 closure went forward. At least one resident accepted an offer to move into shelter, and outreach workers offered phones, storage, and hotel rooms to other residents.

As the city began the closure, about 12 protestors arrived, standing in the center of the encampment. Protestors held signs reading “being poor is not a crime” and “being unhoused is not a crime.”

One protestor, Reverend Ben Roberts, came from Foundry United Methodist Church, which helps low-income people and those experiencing homelessness navigate the ID application process.

“The only way that we end homelessness is to house people. If you’re housed, you are not homeless,” Roberts said, “So we need to put our resources and our leadership into making sure that that is what’s happening, versus this gigantic game of whack-a-mole that only prolongs the problem.”

This is a common refrain from advocates; while encampment closures can make homelessness less visible, they don’t directly move people into housing. While some people have moved into shelter in the last few weeks (though there is no specific number available), the closures have not been coupled with new federal resources to bring any of them closer to permanent housing.

Rather, many people seem to be shuffling around. David Beatty said he lived at the encampment near the interstate for about six months, moving there after another encampment closure. He and another resident were considering moving somewhere in Virginia, where he had lived before, but he was worried about the distance. He has tendonitis, he said, so it can be hard and painful to walk sometimes.

“I don’t know how far a walk that is,” Beatty said.

In total, since Trump’s takeover began, Street Sense has recorded the removal of at least 20 tents and the displacement of at least 20 people in encampment clearings — though that number is probably much higher if clearings of people without tents are factored in.

According to DMHHS, after two weeks of federalization, there were still 68 encampments in the city, with just over 100 residents. The numbers, which are strikingly similar to what the agency reported on Aug. 11, suggest that rather than moving into housing or shelter, most people are just moving around, likely to harder-to-reach places.

There has been a slight uptick in people accepting shelter, according to street outreach workers and the people experiencing homelessness Street Sense has surveyed, but the city did not provide numbers to confirm how many more people have entered shelter in recent weeks. Some people have also temporarily moved into hotels with the help of community groups, though they may not be able to stay long due to limited resources.

Street Sense has also spoken with a couple of people who have chosen to move to either Virginia or Maryland. Last week, local officials in neighboring jurisdictions said they worried about seeing an influx of people if they fled D.C.

Thus far, Hilary Chapman, the housing program manager at the Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments, which coordinates the local Point-In-Time Count, said surrounding jurisdictions haven’t seen a significant increase in people experiencing homelessness, though it could be too soon to tell.

Rather than leave, street outreach providers say most of their clients have chosen to seek new and more hidden spots to spend their time.

Edward Wycliff, director of strategic partnerships and community navigation at District Bridges, said his organization’s teams typically see between five and 20 clients in a single outreach session. Now, it’s down to one or two.

“There are people making themselves scarce,” Wycliff said. It’s been harder for outreach workers to find clients in the last few weeks, he said, which also makes it harder for people to access resources.

His experience aligns with the informal surveys Street Sense reporters have conducted with people experiencing homelessness. After speaking with nearly 70 people over the last two weeks, Street Sense found most people said they tried to avoid attracting the attention of law enforcement as much as possible. People listed a variety of tactics, including avoiding sleeping in exposed places, walking around at night instead of sleeping, and spending more time at drop-in centers. They also said they tried to “act stiffer” or not draw attention to themselves when they see officers patrolling.

“They are responding to this moment with this oppressive situation where people are hunting for you,” Wycliff said. “It makes it hard for the person who is looking for you for something supportive to try to locate you.”

Since the announcement, there’s been an air of fear among advocates, outreach staff, and people sleeping outside about whether this would be a turning point in D.C.’s criminalization of homelessness. While camping, aggressive panhandling, and other actions are currently illegal in D.C., MPD generally does not make arrests for these offenses, though some encampment residents have been arrested at federal closures or involuntarily hospitalized.

In a press conference on Aug. 12, Leavitt said MPD would begin reinforcing laws against camping, and people experiencing homelessness “will be given the option to leave their encampment, to be taken to a homeless shelter, to be offered addiction or mental health services,” and if they refuse, could be fined or arrested.

According to a White House official and public local and federal arrest reports, law enforcement has not made any arrests for homelessness. Street Sense has also not been able to identify any arrests. But, the official said, MPD will begin enforcing local laws against being in public spaces soon. These local laws include D.C. Code 22-1307, which prohibits individuals from crowding or obstructing streets, sidewalks, building entrances, or other passageways, and D.C. Municipal Regulation 24-100, which prohibits the unauthorized use of public space.

It’s unclear how the general surge in law enforcement has impacted people experiencing homelessness, who may be more vulnerable to being charged with some crimes. At least five people who are experiencing homelessness have been arrested since Aug. 11, but all on charges not explicitly related to homelessness.

For instance, law enforcement has emphasized arrests for “quality of life crimes,” which include things like consuming alcohol or marijuana in public. These kinds of arrests disproportionately target people experiencing homelessness because, by definition, the offense must take place in public, which is where people experiencing homelessness spend more of their time.

The D.C. Hospital Association has also not reported a spike in involuntary hospitalizations as of Aug. 20. In the lead-up to the takeover, the Office of the DC Attorney General emailed area hospitals warning them of a spike in involuntary hospitalizations as federal agents fanned out into the city.

Of the more than 70 people Street Sense reporters surveyed in the last two weeks, law enforcement interactions have been inconsistent. Many people did not report increased interactions with law enforcement, but others were asked to show ID or told to move.

For example, Street Sense spoke with a pair of friends who said early on Aug. 13, Secret Service agents woke them and told them they could no longer sleep in Franklin Park. Another man said his friend, who regularly panhandles on a busy street, has been missing since the takeover began.

In some areas where people often sleep, like outside MLK Library, fewer people have congregated over the last few weeks. Some people outside the library, though, seemed relatively unconcerned. Several people said they think officers will focus on violent crimes, and not on people sleeping outside.

Robert Hulshizre said more outreach workers had been by than police. “They already know who’s here; it’s not as if we hide and seek.”

Outreach workers worry about the long-term impacts of the crackdown, which may disconnect people from their service providers and create distrust that will make it harder to ultimately move people into housing.

”For the clients that I can find, or that we can find, the attitude is driven by fear,” Wycliff said. “They’re hearing of and witnessing people in the community or random people on the street being arrested, it’s scary for a lot of clients, it’s scary for a lot of outreach workers.”

For the people most impacted by Trump’s actions, there is a deep understanding of how ineffective they are at addressing the problem. Most have chosen to move to new spots in D.C. Even people who have accepted shelter are not significantly closer to permanent housing.

Abraham decided to move elsewhere in the city because shelter doesn’t work for her, she said. But when asked what she would say to the president — who ordered her forced displacement and equated people like her with criminals — she underscored the futility of his approach.

“In D.C., being homeless is not a crime,” she said. “They need to provide us another option, and they’re not doing that, they’re just saying get out of here.”

Madi Koesler, Katherine Wilkison, Mackenzie Konjoyan, Nina Calves, and Jelina Liu contributed reporting.

With your help, we pursue stories that hold leaders to account, demystify opaque city and civic processes, and celebrate the idiosyncrasies that make us proud to call D.C. home. Put simply, our mission is to make it easier — and more fun — to live in the District. Our members help keep local news free and independent for all: