Go ahead and file your taxes, says D.C. CFO amidst confusing fight over tax law

No pause or delayed deadlines are now expected.

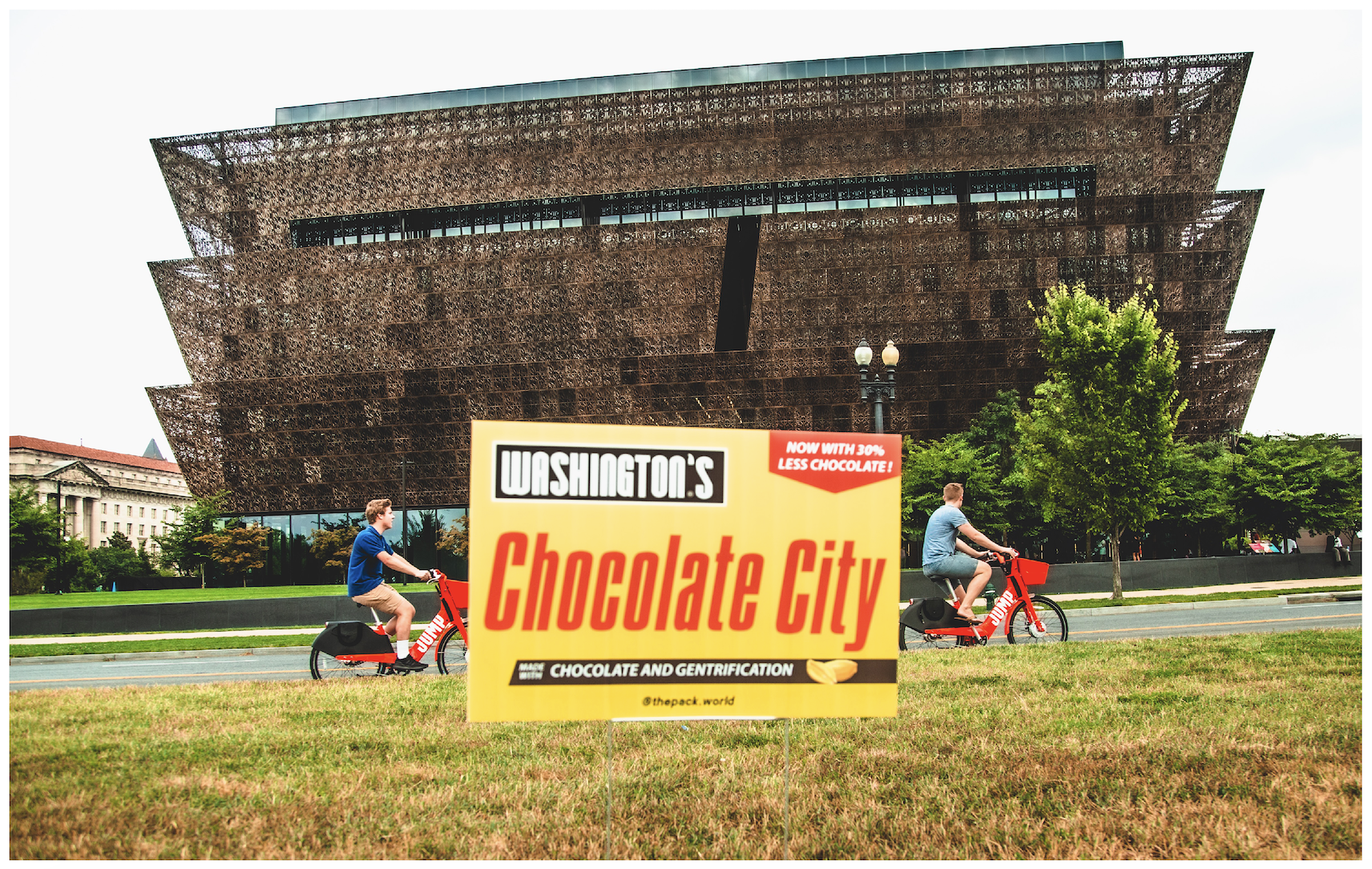

Gentrification in the District has displaced large numbers of longtime residents. What pieces of a Black utopia remain?

When people first started using it, the moniker “Chocolate City” was about demographics — D.C. was a statistical anomaly for a major U.S. city at the time. People who grew up in Chocolate City have a shared upbringing rooted in specific cultural, academic, community, sports, arts, and political experiences. It existed as a Black utopia for residents.

I grew up in Woodridge, more colloquially known as 18th and Monroe or the 1-8 Zone, depending on who you ask. It was the early 2000s, and many of my neighbors, police officers, firefighters, councilmembers, and educators were Black. I remember singing the Black National Anthem, Lift Every Voice and Sing, each morning at school and at every elementary school program.

On Saturdays, I’d tag along with my parents to Hains Point or watch summer league basketball in Southeast with my friends. Little league football games at Taft, Lamond Riggs, and Beacon House felt as high-stakes as the NFL.

I remember the unofficial block parties where kids ran through alleys while pocket go-go blared in the background. During big summer parties like Unifest and the Caribbean Day Festival, I promised my parents I’d stay out of trouble.

I didn't meet a white person my age until high school. And it wasn't until I ventured to West Virginia University that I realized this was not the case for some of my Black peers from New York, Philly, Virginia, Pennsylvania, North Carolina, Florida, and so on.

D.C. residents lived this reality for 50 years, and as a result, the history and cultural norms of this city stem from its Black culture. To say D.C. is no longer Chocolate City also ignores the nearly 300,000 Black people who still call this city home — many of them creating institutions that uphold the cultural roots of the city.

D.C. became the first majority Black city in the United States in 1957. By 1971, the city’s Black population was over 70 percent. In 1975, popular funk band Parliament released an album entitled “Chocolate City,” highlighting D.C.’s thriving Black culture born in response to white residents' flight to the suburbs in the ‘60s and ‘70s. This ultimately cemented the city’s nickname in the history books.

I’ve experienced the unique beauty of Chocolate City, growing up in close-knit communities that supported various aspects of my life. But I’ve also witnessed how much the city has changed over the last 20 years.

In 2011, D.C.’s Black population fell below 50 percent for the first time in about 50 years — 20,000 Black residents were displaced between 2000 and 2013, as D.C. had the highest percentage of gentrifying neighborhoods in the country.

There were small signs in the beginning: more bike lanes and Whole Foods locations, the streetcar on H Street — all while an influx of white residents moved into neighborhoods you couldn't pay them to walk through a decade earlier. Fast forward to 2018, the District approved $300 million to redevelop The Wharf and $82 million to make Union Market what it is today, while development in neighborhoods such as Barry Farm were stalled.

Today, D.C.’s Black population is roughly 45 percent of the city’s population. Still, D.C. history is Black history, and no amount of gentrification can change that fabric.

In the modern context, Chocolate City describes our culture, rather than our demographics. Culture and community do not have units of measurement.

City officials understand this, which is why Black aesthetics and achievements are used to attract transplants. For instance, look at the city’s relationship to go-go. In the 2000s and early 2010s, go-go venues faced systematic shutdowns and police crackdowns because of perceived violence, effectively pushing the genre out of D.C. But in 2020 — in response to the Don't Mute D.C. movement — it was made the official music of the city.

Now, go-go is seen as something palatable and marketable that city officials embrace. It's one of the biggest examples of new demographics not being able to erase D.C.’s Black culture, no matter how hard they may try.

The Black activism of yesteryear laid the foundation for the progressive politics that run the city today. Even the progress the city has made with home rule stands on the shoulders of Black advocacy.

When Donald Trump instigated a federal takeover of the District, Black residents were on the frontlines, creating community resources to share with our youth and immigrant communities.

When D.C. endured the longest federal shutdown in our country’s history, Black residents were pooling resources to support federal employees who were not getting their paychecks.

Even though our numbers are smaller, our impact remains large. Chocolate City still exists because Black residents continue to live, persevere, cultivate culture, and survive in this city.

And as long as Black people exist in D.C, so does Chocolate City.

With your help, we pursue stories that hold leaders to account, demystify opaque city and civic processes, and celebrate the idiosyncrasies that make us proud to call D.C. home. Put simply, our mission is to make it easier — and more fun — to live in the District. Our members help keep local news free and independent for all: