Go ahead and file your taxes, says D.C. CFO amidst confusing fight over tax law

No pause or delayed deadlines are now expected.

Eleven D.C natives on how they remember their city.

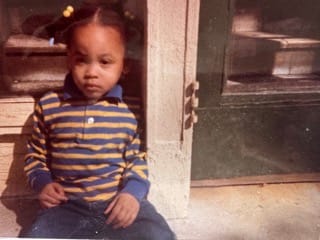

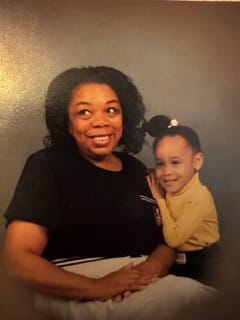

In the early 2000s, I remember hearing that the Columbia Heights Metro was finally coming. The idea of walking a single block to the train instead of riding two buses clear across the city to get to school felt like a small miracle; convenience carried the promise of possibility. I didn't know it then, but that shiny station marked the first wave of change. For a while, life kept its steady rhythm — familiar and dependable. But after I left for college I returned to find the landscape shifting beneath my feet. The laundromat where I had spent years playing pinball, clearing lint traps, and racing laundry carts with neighborhood kids had vanished. The Woolworth’s department store disappeared too, taking with it memories of family portraits with my grandmother — my side ponytail and yellow shirt glowing beneath warm studio lights, our smiles easy and unguarded.

One by one, the places that held our stories gave way to something new. Even the Tivoli Theater transformed. Each time we walked past the building my grandmother recounted stories of paying 25 cents to watch movies all day. For decades, the building itself looked suspended between eras, its once-grand face marked by burn scars; its old movie posters faded and curling at the edges.

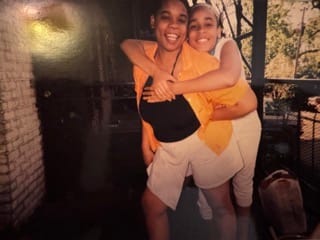

India Kea, Park Road, 1989; Ruth Kea and India photographed at Woolworth’s, 1990; India Kea and Alesia Kea on Park Road, 1998 (Courtesy of India Kea)

The final wave came quietly but landed heavy when my mother told me we had to move. I had lived in that apartment since the day they brought me home from the hospital. My grandmother had been there since the 1970s. The numbers told the story plainly: our rent jumped from $850 to $2,000 in just three months. Change is inevitable, I told myself, trying to make peace with the tide. At the time, I truly believed we would be able to keep up.

From changing faces and street signs to rows of newly planted trees, we asked D.C. natives from across the city to reflect on what it was like growing up here, and the pivotal moments when they realized their hometown was no longer the same.

"One vivid memory is of Braids Unlimited near U Street, where I had my hair braided every year while in college and university break. It was once a bustling establishment with 12-14 braiders, always filled with customers. I loved going there and seeing seeds being sown into those who supported the community. However, rising rent prices made it unaffordable for the owner to continue to lease, leading to an abrupt relocation to First Street NW. Unfortunately, the same situation occurred again there.

This is just one example of countless small businesses being pushed out by rising rents and upscale boutiques, resulting in a dramatic shift from a community of people of color who once owned and supported a significant amount of businesses to an influx of newcomers."

"I first noticed D.C. was changing during my senior year in high school. At that time I went to Cardozo Senior High School where I graduated from in 2005. My guy at the time was from Uptown. One evening, we sat in the car near U Street deep in conversation while smoking a spliff. We suddenly noticed something was off about the neighborhood. It was a newer building being built right in the heart of this historic community. It looked so out of place.

My dude went into full lecture mode on how D.C. is being gentrified and how we needed to buy up the block ASAP. We were around 17, and he was right! After graduation, I went to Miami for college. Each time I’d come back to visit home, I noticed more construction happening throughout Northwest. Black families began migrating to other places due to rent increases along with persistent new buyers pressuring longtime home owners to sell.

Each summer less people from the communities I’d frequent were outside. The essence of Chocolate City began to sadly fade away."

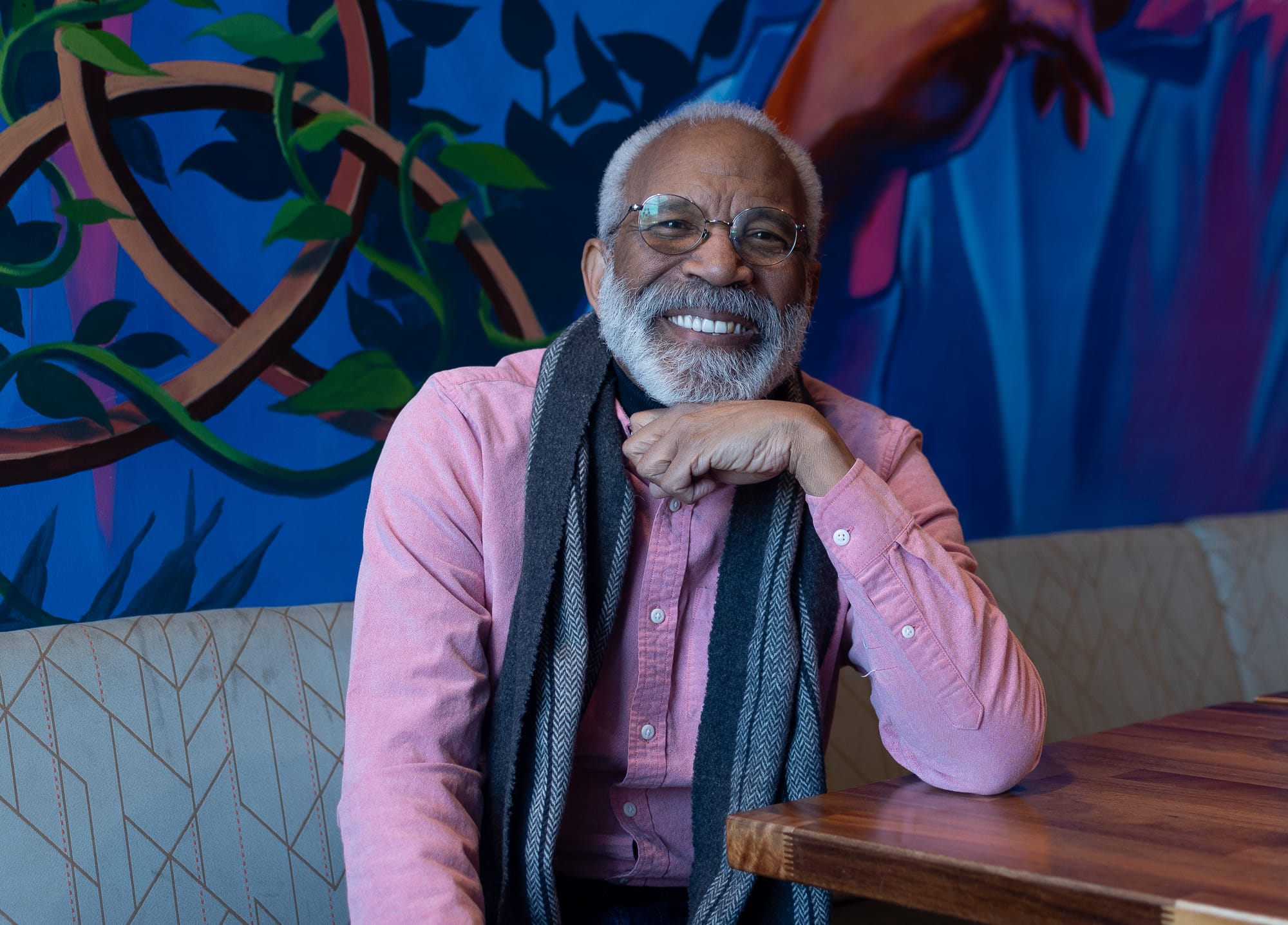

Damión Perkins (India Kea)

"I realized D.C. had changed when I came home from college and U Street NW, where I had been going to the club during the '90s, now had police officers walking the block. They were on almost every corner and also patrolling the street. I had to pause and look around for a minute. Then I started counting how many I saw in a certain amount of time.

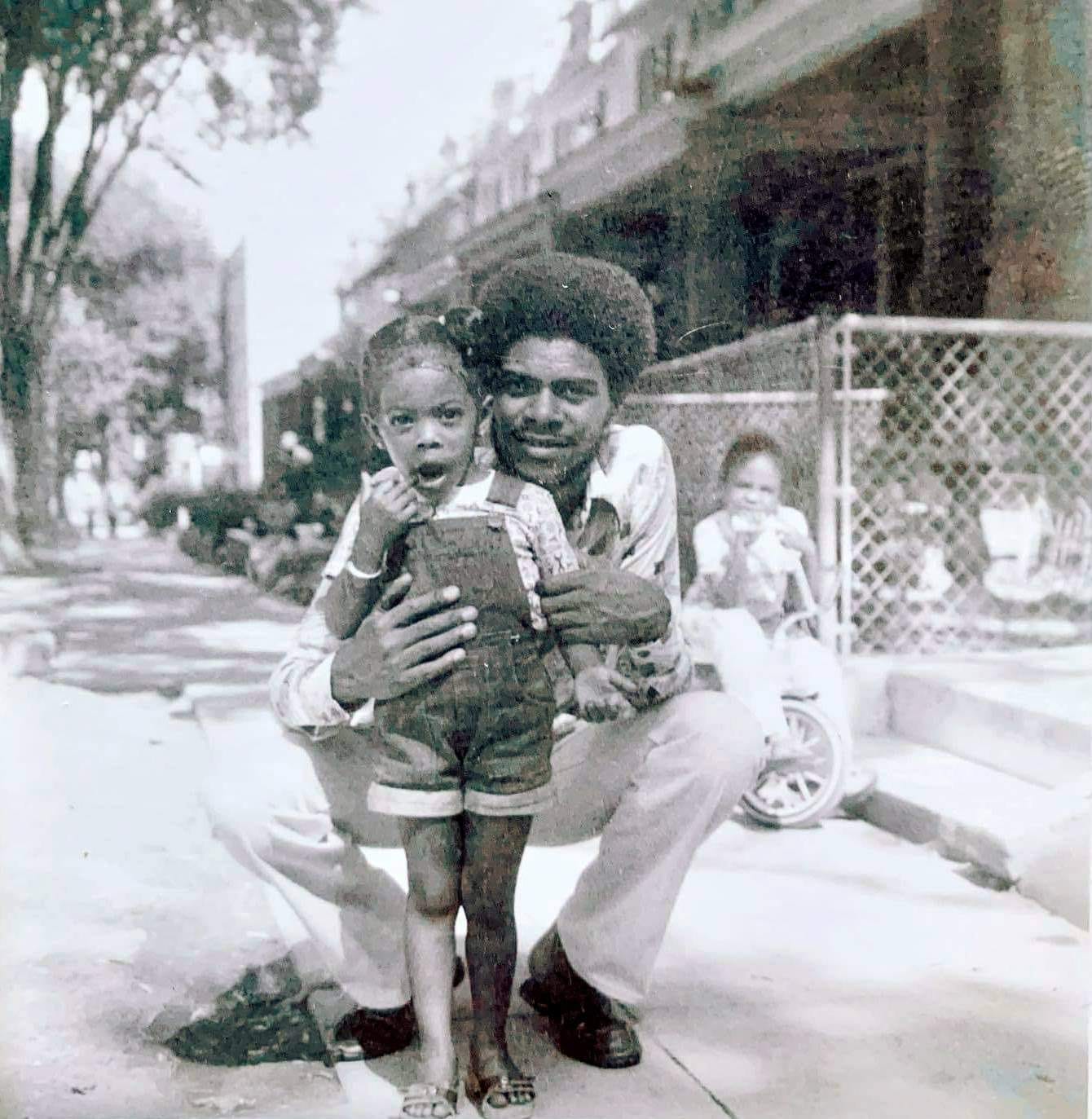

Damión Perkins & Patreda Perkins, Classics Nightclub, 1997; Damión Perkins & Mike Johnson, Marrietta Place NW, 1976 (Courtesy of Damión Perkins).

I remember going to Republic Gardens, Pure Lounge, and also to my hairdresser on U Street. I would go to Ben's Chili Bowl, the Lincoln Theater or just walk around U Street during the day and venture back down there for the clubs at night. I don't ever remember seeing any police officers, especially on foot even when I was leaving the clubs early in the morning to go back home! Eventually they closed most of the clubs I frequented and started building more condos in the area. That was the end of that area as I knew it."

Georgetown neighborhood, Wisconsin Avenue NW DC, circa 1984 (The People’s Archive at DC Public Library); Afra Abdullah (India Kea).

"In the '90s, my world was Georgetown, specifically The Shops at Georgetown (now Pinstripes) and The Cliff. I frequented Bohemian Caverns — my godfather is Dave Yarborough, a prolific jazz musician and educator who has been instrumental to jazz education in D.C. — as well as Twins Jazz and a more vibrant U Street nightlife scene. I also fondly remember summer concerts at Carter Barron Amphitheater and the Caribbean Festival on Georgia Avenue."

"The real shift occurred in the mid-2010s. The Wharf rose, Navy Yard filled with apartments and restaurants, and Manor Park and Takoma Park became 'hidden gems.'" — Afra Abdullah

"I left D.C. for college in New Jersey in 2010, and every time I came back home, something felt different. My sisters and I used to joke that once you started seeing premature trees being planted, you knew the neighborhood was about to change. Each summer, a new set of trees appeared across the city.

I grew up in Langdon Park in Northeast D.C., a community with a lot of seniors. When they passed, their homes were often renovated and sold to younger, liberal couples, not the same people who grew up throwing old-school cookouts with go-go blasting, kicking it with neighbors who felt like family. Prices went up, local corner stores disappeared and were replaced by chain stores, and the neighborhood’s energy shifted. There were fewer kids outside just being kids, and more young people getting pulled into crime."

"I went to St. John’s College High school. I remember my Algebra II teacher said that she lived in Trinidad and I was like, 'What now? Is everything okay?' It was so confusing."

— Lauren Wells, Brookland

Troy Cureton (India Kea); Arthur Capper Dwellings in 1980 (The People’s Archive at DC Public Library).

"In the early 2000s, I would notice many of the famous or infamous neighborhoods in the city like Arthur Capper public housing or as it’s better known “Cappers” and Kentucky Courts either being demolished or redeveloped as a part of the city's urban renewal agenda. As someone who grew up adjacent to many of the public housing apartments that were being demolished and as someone who knew people from those buildings, I was rather ambivalent towards their destruction.

I didn't know if I was happy that these project buildings that were connected to years of crime and urban decay during my childhood were being destroyed or if I was sad for some of the people who were being displaced. I can honestly say looking back that it was a combination of both."

Dwayne Lawson-Brown (India Kea)

"I remember being 16 or 17, my Uncle Josh and I were walking around Alabama Avenue and Wheeler Road when we walked through the alley as a shortcut. I hadn't taken this particular cut before, and he was like "Aye, don't walk this route alone." Fast forward, and I'm 20. It's late, and I'm walking to my mom’s house. I take the cut, and I got robbed. I've always figured they needed it more than I did.

A few years later, I'd say 2007, I'm around that same area waiting at the bus stop. I see a white couple jogging down Alabama Ave. They take the same cut down the alley. Headphones in. No fear."

Artis Washington (Photographed by India Kea); Artis Washington, Mayor’s Office circa 1970 (Courtesy of Damion Perkins).

"I noticed it when I visited my old neighborhood. The home at 1537 Congress Place SE was demolished and Townhouses were built and the street was renamed. I started seeing block by block townhouses and the Shopping center Businesses at Alabama Avenue and Stanton Road changed too. Then I started seeing white folks walking around the neighborhood with baby carriages. I believe that this was the late 1990s." —Artis Washington, Congress Heights

"I first noticed that D.C. was changing in the early 2000s when a bunch of people from my neighborhood started moving out to Maryland. Once the go-go bands started playing out there more, I knew things were different."

Arnold Murray (India Kea); Aerial view of Martin Luther King, Jr. Avenue circa 1980 (The People’s Archive at DC Public Library).

"I first noticed ... the destruction of homes as a result of the building [of] I-395/I-695, between 1966 and 1973. It was devastating to witness. All of those people who lived there for generations had to leave — their homes destroyed." — Arnold Murray, Dupont Park

This story was updated to correct a quote by Sheronda Carr that was misattributed to Damión Perkins.

With your help, we pursue stories that hold leaders to account, demystify opaque city and civic processes, and celebrate the idiosyncrasies that make us proud to call D.C. home. Put simply, our mission is to make it easier — and more fun — to live in the District. Our members help keep local news free and independent for all: