D.C. police got me buzzed to help stop drunk drivers

A dispatch from MPD’s wet lab, where police train to spot impaired motorists.

“I’m going to get you another cold one,” the police officer said.

I wasn’t about to say no. The decor could best be described as office-space drab; the massive flat-screen TV wasn’t turned on to provide any mindless distraction; and the bar snacks, well, let’s just say tiny bags of Pirate Booty don’t do much after your second drink in 20 minutes.

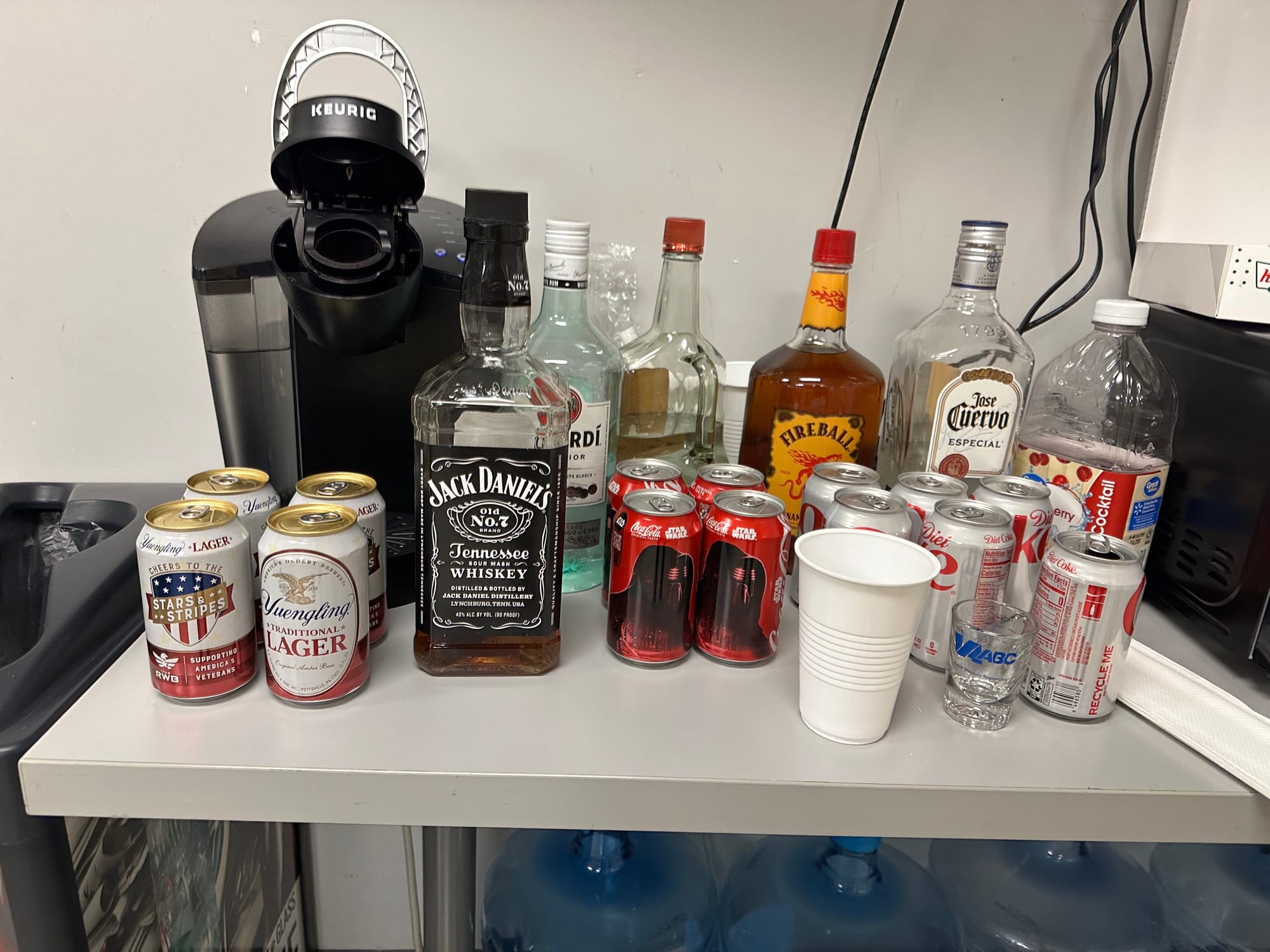

So yeah, another beer sounded just fine. It was probably better than the alternatives, anyhow. There were a few bottles of generic vodka, whiskey, and tequila, some mixers, and… Fireball.

But there I was, as one of my fellow drinkers pointed out, “in the name of science and safety.” On a weekday. At 10:30 in the morning.

Welcome to D.C.’s wet lab.

The drinks are mediocre, and it’s certainly not going to be a destination for the city’s scenesters. But here the alcohol has a higher purpose: Training police cadets and officers how to administer field sobriety tests and pull impaired drivers off the road.

And for that, nothing substitutes better than actual human subjects — last week, that was me and four newfound friends. The Metropolitan Police Department often recruits its subjects from within the D.C. government, but will occasionally allow members of the general public — and pesky reporters — to take part. (Two of my fellow drinkers that day work for the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, where they run tests on blood and urine samples in impaired driving cases. The others were tech workers who found out about it from a friend.)

The lab is a small office in a hulking building on New York Avenue NE on the outskirts of the city, home to MPD’s Traffic Safety and Special Enforcement Section. We weren’t told what to drink, but everything we imbibed was duly recorded down to the ounce. (The police don’t refer to them as drinks, but rather “doses.” You're not drinking, but rather being dosed.) Every now and again we were breathalyzed to check for blood-alcohol content. The goal is for each participant to be somewhere slightly different along the scale.

“I’m not going to get you hammered, because that’s obviously easy [for the cadets to spot]. But I’m going to get you at a certain [BAC] so when they train they can know, ‘Hey, is he just below the limit? Or above the limit? Or clearly above it?’” explained Sergeant Terry Thorne, who leads MPD’s traffic enforcement efforts and runs the lab. (Other states have similar wet labs; Maryland has even run green labs, where officers learn to spot drivers who are high.)

I had three beers before I was told to stop. For another participant, it was five mixed drinks — each with a shot of vodka. A third went for four tequila drinks. And the bravest among us had seven mixed drinks — all with Fireball in them. (Blood cinnamon content: high.) There was one control subject who didn’t have any drinks at all.

Once properly dosed and maybe a little chattier than when we started, we were led into a large garage where 15 police cadets awaited us. In small groups, they conducted the Standardized Field Sobriety Tests on each of us. We were told to walk in a straight line with our feet toe to heel, turn around, and walk back. Then we were asked to lift one foot off the ground and try to hold our balance while counting out loud.

But Thorne says the biggest focus is teaching cadets how to spot impairment just from a person’s eyes. “The eyes won’t lie. When you drink, the alcohol goes to your brain. And as your eyes move back and forth, they’re going to lock out and you’ll have some involuntary jerking,” he told me.

That tell-tale jerking is known as nystagmus, and the cadets checked for it by asking each of us to follow the tip of a pen as it moved in and out of our field of vision.

Thanks to my three beers, I had a buzzy confidence I could beat the tests. Balancing on one foot seemed relatively easy; I thought I walked the straight line with calculated precision; and it felt like my eyes easily followed the pen as it crossed from left to right and up and down. But I was also wracked with anxiety, fully aware that my brain and body were probably more uncoordinated than usual. (My slightly dramatic turn during the line-walking was apparently a hint of impairment.)

After we broke for lunch, everyone came together in a conference room for what could best be described as the moment of judgment. The cadet teams offered their readouts on each drinker, detailing what they noticed during the field tests and declaring whether they would have arrested us or not. There was general consensus that the first few people were impaired.

In D.C., it’s illegal to drive if you’re impaired at all. (Legally speaking, impaired means you have any substance in your system that affects your ability to operate a vehicle in a way that can be “perceived or noticed.”) A BAC of .07 or below can get you charged with driving under the influence (DUI), while .08 and above is driving while intoxicated (DWI). The woman with four shots of tequila in her system was determined to have a blood-alcohol content of .12, which is considered significant impairment.

But there were cracks in the consensus when the cadets got to me. Four of the six teams declared I was impaired and arrestable, but two disagreed. “You let this guy go?” one cadet asked, almost incredulously.

“[They] made a decision,” Thorne interjected. And it was a tough one. He later revealed that my BAC was between .05 and .06, making me legally impaired. But some people at that level might still be able to navigate the walking and balance tests.

And ironically, almost all of the cadets declared that the control subject — the woman who didn’t drink at all — was probably impaired and should be arrested.

“She fooled you all,” said Thorne. “She made you think. This is meant on purpose. I want you to learn today.”

As the wet lab came to a close, the split determinations made me wonder, how open is all of this to interpretation?

“You’re seeing just the battery of tests right now. But in reality, the investigation that the officers are going to do is not just this small piece,” said Melissa Shear, the acting director of D.C.’s Highway Safety Office. “It’s important, but it’s not the only thing they’re going to look at.”

Shear and Thorne told me that officers also rely on what they see a driver doing before they’re stopped and what they might notice (or smell) from the first contact with the person. And Thorne noted that this was only the first day of training; the next day would focus more intensely on detecting impairment through the eye tests, which are the most reliable indicator.

“The science supersedes the interpretation,” he said.

And everything we experienced is only used to justify the arrest; building the case for a prosecution will involve blood, urine, or breath tests conducted at a police station. It’s those tests that formally determine a BAC that can be used in court. Officers on the street don’t carry breathalyzers, though. Field units are not admissible in court because of concerns about accuracy. (Back in 2010 and 2011, hundreds of DUI cases in D.C. were thrown into jeopardy when it was revealed that the units officers were carrying hadn’t been properly calibrated.)

Thorne says the field sobriety tests are a critical tool in making D.C.’s roadways safer. (There’s also additional training to spot impairment from drugs other than alcohol.) There were 47 traffic fatalities in D.C.involving alcohol between 2016 and 2023, according to data collected by the Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments. That includes cases like Jesus Antonio Llanes-Datil and Thomas Dwight Spriggs, two unhoused men who were killed in 2019 when an impaired driver barreled into the park they were sleeping in. And in 2023, an impaired driver with a history of DUIs slammed into a Lyft while speeding down Rock Creek Parkway, killing three people.

“Impaired driving has been one of the top threats to our roadways for decades. A third of all roadway fatalities are caused by an impaired driver: drugs, alcohol, or a combination of the two,” Shear told me. (Keenly aware of these facts, every participant in D.C.’s wet lab gets a Lyft credit so they can get home safely.)

But D.C. law doesn’t limit DUI and DWI charges to drivers; riding a bike or scooter (or horse drawn carriage) after having too many drinks is also unlawful.

Enforcement and prosecutions have also increased in recent years. There were 545 traffic-related convictions in D.C. in 2022, most for impairment. In 2023 that went up to 752, and in 2024 it was 1,592.

All of this felt even more relevant given that we’re entering the holiday season, when drunk driving incidents and arrests tend to tick up.

“This,” Thorne told the cadets as the day of training ended, “is the beginning stages of you learning to save lives on our roadways.”